Wingfoot Air Express

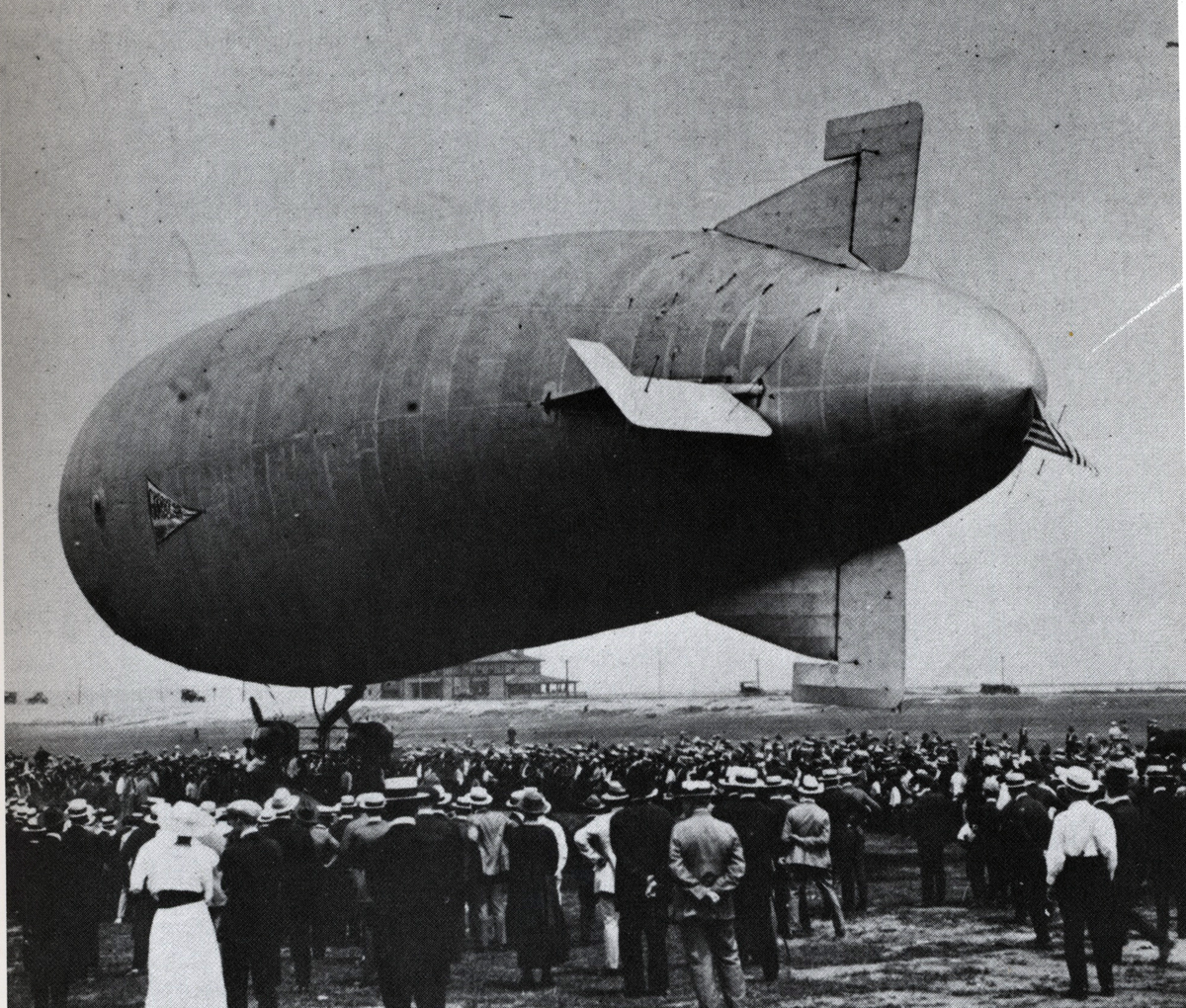

Wingfoot Air Express, Grant Park, Chicago, 1919. Photo credits: steampunkchicago.com

Original photo in Illinois Trust & Savings Bank "The Columns", special issue, July, 1919

[The photo above is not the photo originally chosen to introduce the Wingfoot Air Express. For an explanation, see "Endnote", below.]

Construction

Almost nothing about the Wingfoot Air Express is found when researching it. Even the "Flightglobal Archive" has nothing about it. It is said to be the "first Goodyear blimp" but that is wrong because the Wingfoot Air Express was built in 1919 and Goodyear began making balloons in 1912 and began building blimps for the US Navy in 1917. Part of the problem of researching the Wingfoot Air Express is that the term "Wingfoot Express" was used for a number of Goodyear products including a truck line in 1917 and the Wingfoot Air Express is sometimes misidentified as the "Wingfoot Express". Indeed, the term "Wingfoot" refers to the logo of the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, the trademarked "Foot of Mercury". But one finds absolutely nothing about the Wingfoot Air Express dirigible/blimp, even on the Goodyear corporate website! To make matters worse, the Knabenshue passenger airship "Pasadena", later renamed the "White City" employed for passenger rides at the Chicago Amusement park of the same name is sometimes misidentified as the "Wingfoot Air Express". (See for example the leech photo-sales site of public domain photos, "Getty Images".)

What is known about the Wingfoot Air Express is that it was built and stationed at the White City Amusement Park Airship Shed in Chicago as the Goodyear Wingfoot Lake airship facility was not begun until 1917. Goodyear already had a contract with the US Navy for 9 of the 16, B-Type Airships the Navy had ordered. (The Navy order went to several companies since no single company could produce 16 blimps in the desired time.) The B-1, built by Goodyear, had to be assembled at the White City shed because the Wingfoot Lake shed was not ready.

The actual date of construction of the Wingfoot Air Express is unknown but it was ready for trial flights in July, 1919. The last B-class Blimp for the Navy was delivered in June, 1918, but the Wingfoot Lake facility owned by Goodyear was also under contract for a Navy LTA training program, and Goodyear received additional Navy contracts for the new C-Class and D-Class blimps so there clearly was no capacity at Wingfoot Lake for construction of the Wingfoot Air Express, a commercial venture. It is presumed that Goodyear retained its arrangement with White City for its fledgling commercial blimp activity, because the airship was built at the White City Airship Shed.

Nevertheless, the Wingfoot Air Express is said to have been designed with some "innovations" not previously tested. It was reported to be the first Goodyear blimp with separate gas ballonetes (in addition to the standard air ballonetes used for maintaining envelope pressure), and two Gnome Le Rhône rotary engines suspended from the envelope, aft of the control car rather than mounted on the control car as was the usual design. Presumably, this provided increased safety to the passengers as well as reducing any direct vibration from the engines to the control car. (There is a fine short video of this type of engine here: 1918 Gnome LaRhône rotary.)

The use of separate gas ballonetes had two apparent safety benefits. First, if any one gas ballonete began to lose its gas, the other gas ballonets would be unaffected thus limiting the lost of lift. Second, the the remaining gas in the envelope would not be free to redistribute itself within the envelope and the envelope would be somewhat more likely to maintain its shape, and not "fold" as badly as gas was lost. This would permit the blimp to maintain a flyable shape long enough to permit a safe decent.

Wingfoot Air Express Control Car and Engines. Photo credits: Public domain

The Wingfoot Air Express was 158 feet long, 33.4 feet in diameter, had a 95,000 cu ft gas capacity and its lift gas was hydrogen*. The two Gnome Le Rhône rotary, air cooled engines provided 110hp each. A 34 foot long open gondola had a passenger and crew seating capacity estimated at 6 (2-3 crew, 4-3 passengers).

(*I should point out that at this time in US history, the capacity to produce helium was not adequate for LTA operations, even by the US Army and Navy, so all airships of this era relied on hydrogen. Helium production in the US did not ramp-up until just after WW I, when WW I investments permitted the large scale production of Helium beginning in 1919.)

Operations

By the design appearance, the Wingfoot Air Express was apparently intended to be a commercial, passenger carrying craft. At this time in US airship history there was much talk of passenger and mail transport between cities.

The maiden flight was on July 21, 1919. The White City Airship Shed on the south side of the White City Amusement Park, faced a large, open field continuing to the south - part of the amusement park property. The airship was hauled out of the shed, and the Goodyear pilot, and two Goodyear mechanics climbed on-board. An Army Air Service Colonel, Joseph C. Morrow, was also a passenger on the initial flight. (It is unknown if the Army Col was observing the flight for potential Army contracts, or if he was simply present for the "ride".) The airship was launched and after apparently proving to be operational, headed north to Central Chicago roughly paralleling what is today Martin Luther King Drive.

The Wingfoot Air Express arrived at Grant Park, which at that time was a popular airfield and airmail terminal, where she was met by a ground crew and safely hauled down. The maiden flight was about 7 1/2 miles.

Having completed its maiden voyage, the airship apparently passed inspection, she was launched a second time at about noon, northbound with an undetermined number of passengers. She was piloted roughly north along the shore of Lake Michigan, turning around at about Diversity Ave and returned to Grant Park about 3 pm.

At about 4 pm, she launched again from Grant Park for the return trip to White City.

Demise

On the return flight to White City, the story is told that passenger William Norton, a photographer, asked the Goodyear pilot, John Boettner, to deviate from the planned route so he, Norton, could capture some aerial photos of the Chicago skyline. The airship was directed toward what is known as the "loop', the large area of central Chicago, the commercial area full of skyscrapers.

Just before 5 pm, while the Wingfoot Air Express was at about 1200 feet over Chicago, fire broke out near the stern. Witnesses say the blimp, fully engulfed within seconds, buckled in the middle, jack-knifed, and plummeted earthward. The passengers, all with parachutes, attempted to jump. Four were successful, while one passenger, Earl Davenport, a publicist for White City became entangled in the ships rigging. Another parachute, that of Goodyear mechanic Carl Weaver, was ignited by the burning debris from the falling airship and he fell to his death. Three parachutes made it to the ground, though one, the photographer, Norton, landed hard, broke his legs, sustained serious internal injuries, and he died the next day. The pilot, Boettner, and one of the mechanics, Henry Wacker, survived, the only two on the airship to survive the crash.

Ignominious End

The Wingfoot Air Express gondola, engines, fuel tanks, rigging, and the remains of the burning envelope crashed onto the roof of the two-story Illinois Trust and Savings Bank, crashing right through the building's giant skylight where nine bank employees died in the resulting inferno.

Wingfoot Air Express ceased to exist, the bank was cleaned up and even opened the next day. Funerals were quietly held. Investigations resulted in no determination of the cause of the fire and though some Goodyear employees had been arrested, including the pilot, Boettner, no charges were ever filed. The story faded quickly from the news. Even today, there is no mention of the the airship or the disaster on the Goodyear website. It's as if the Wingfoot Air Express never existed.

There are plenty of website articles about the crash of the Wingfoot Air Express and the chaos at the bank the day of the crash. You can research those on your own. This website is dedicated to the airships and where the activity took place so no links about the disaster will be presented here.

Sites of Interest

Chicago:

The launch site at White City Amusement Park, Chicago, the landing site at Grant Park, and the crash site of the Wingfoot Air Express are all located!

White City

This first site is the location of the White City amusement park airship shed:

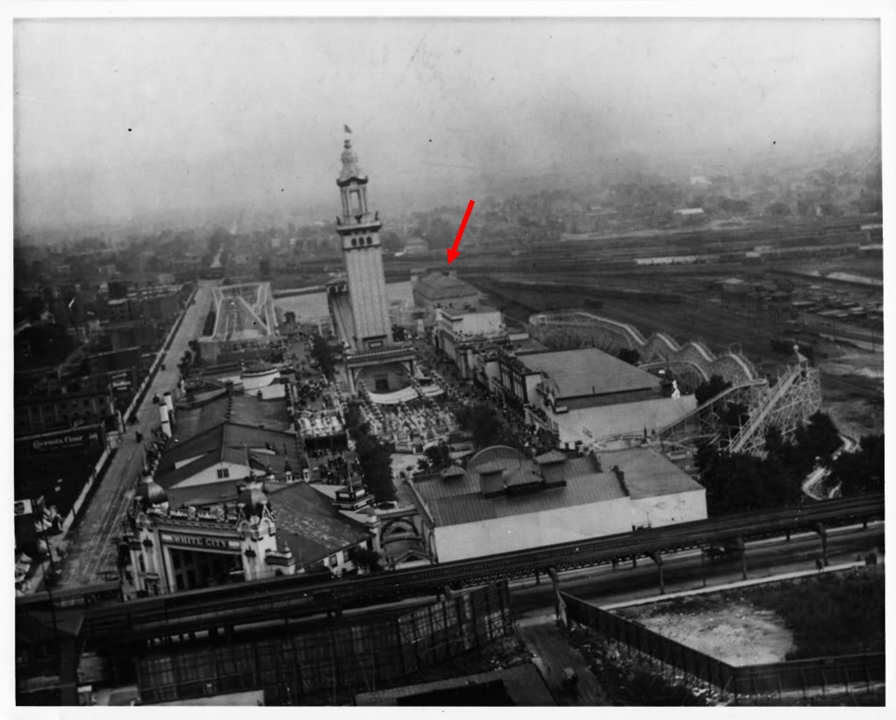

White City, c. 1912, looking south from 63rd St. Arrow points to the Airship Shed. Photo credits: Public domain

In the undated photo of White City, Chicago, above, the Airship Shed is identified by the arrow. This is the shed used by Roy Knabenshue in his "White City" passenger airship (formerly the Pasadena) in 1914. Airships were long a part of the "show" at White City, Chicago. An open field existed south from 65th St south to 66th St., a near perfect place to conduct small airship operations in a densely populated area.

The location of the hangar at White City, Chicago was at (Lat Lon) 41.776521 -087.616934, (Click here to View in Google Maps). The site today is the "Parkway Gardens" apartment complex. Imagine how many residents there have absolutely no idea the rich airship history of the area in which they live!

Grant Park

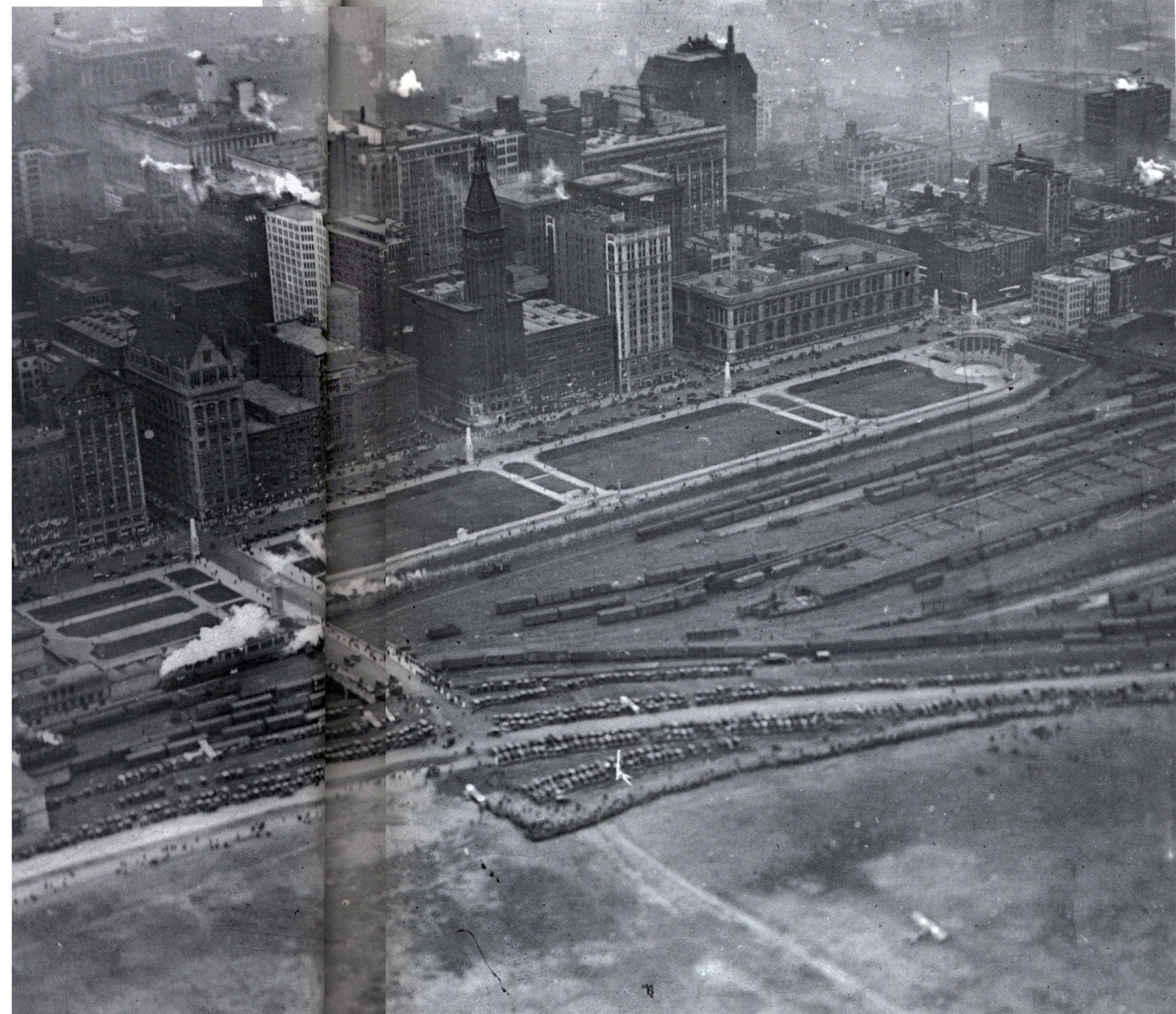

Grant Park at the time, where the Wingfoot Air Express landed and a flourishing airpark operation and was a U.S. Mail airfield. The site of the landing is now the Petrillo Music Shell open-air concert complex and Butler Field.

1919 photo of the Chicago skyline and Grant Park - landing site of the Wingfoot Air Express. Photo credits: chicagology.com

The airfield is just visible in this photo even an airplane is seen. The landing site of the airship would have been near the lower-left corner of the image.

The location of the Wingfoot Air Express landing is at (Lat Lon) 41.879163 -087.619233, in what is now Butler Field and the location of the Petrillo Music Shell:

.

Location of where the Wingfoot Air Express landed in Chicago. Google Maps.

Imagine how many concert-goers today have no idea of the rich airship history in their very midst!

Wingfoot Air Express Crash Site

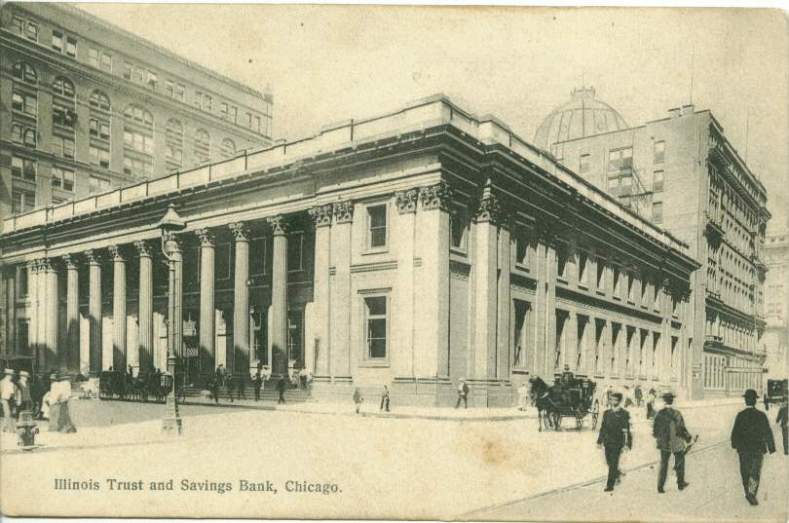

On July 21, 1919, the Wingfoot Air Express crashed into the 2-story Illinois Trust and Savings Bank which at the time looked like this:

Illinois Trust and Savings Bank Post Card. Photo credits: Public domain

The location bank was at (Lat Lon) 41.878398 -087.631863, today the site of the 20 story Wintrust Financial Corporation. The original building seen in the photo of the postcard above was demolished in 1924. (Click here to View in Google Maps).

I leave you with this drawing of the dreadful incident from the July, 22, 1919 Chicago Tribune - not for any morbid reasons but to simply close this tragic, long forgotten episode of airship history.

Photo credits: 1919 Chicago Tribune

Footnote: I was not able to establish a purpose, or reason for the development of the Wingfoot Air Express blimp. Companies do not typically invest dollars into technology demonstrations unless they have reason to believe there is a potential buyer at the other end! Here we have two possibilities. Either Goodyear was under contract with the owners/operators of the White City Amusement Park of Chicago to design and build a commercially viable blimp to be marketed at a number of amusement parks, or the US Army was seeking to "piggyback" off the interest in and purchase of militarily useful blimps, first to the US Navy and next to the US Army. Hmmm.

I know from the record that the US Navy procured 16 B-class blimps in anticipation of needed support to WWI, and that Goodyear built 9 of those B-Class blimps about at the same time as the Wingfoot Air Express was built. I also know that one of the passengers, the only "non crew" of the maiden flight of the Wingfoot Air Express, that initial flight from White City to Grant Park, was a Colonel Joseph C. Morrow of the US Army Air Service! I don't know why Col Morrow was on the maiden flight of the blimp! Was he there to assess the air-worthiness of this "new" configuration of airship for the US Army for a potential contract, or did he "just happen" to be at the White City Amusement Park at 9 am on July 21, 1919 and was simply "invited" to fly on the maiden flight of an untested aircraft?

Endnote:

When I first introduced this article on the Wingfoot Air Express, I posted on this page a nice photograph of the Wingfoot Air Express taken on the grounds of Grant Park in Chicago. I painstakingly located the approximate spot the airship was moored by examining the buildings in the background of the photo. After all, this site is about where airship activity took place, not so much about the airships themselves. In March, 2019, I received a terse email from James M. Gampper claiming copyright to the nearly 100 year old photo. Therefore I immediately removed the photo from this page based on his objection.

Photo credits: Bill Welker. eMail from James M. Gampper

Mr. Gampper is the grandson of airship pilot Frederick K. Gampper who worked for the GoodYear Rubber Company. Frederick Gampper was the chief pilot of the Wingfoot Air Express. The day of the fateful crash of the airship, pilot Fred Gampper was reportedly too "heavy" given the airship's load that day, so a lighter pilot made the flight. Frederick Gampper was not even on the airship that day.

None of these facts about 1920's pilot Gampper explain why a grandson, descendant James Gampper, would not want the 100 year old photograph of the Wingfoot Air Express to be seen on websites about the Wingfoot Express. Mr. Gampper has been successful in his apparent attempt to expunge the 100 year old photo from the Internet so no one can enjoy it, the photo is no longer found on Wikimedia at

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wingfoot_Air_Express_(8).png#/media/File:Wingfoot_Air_Express_(8).png

...or in the video seen briefly at the very beginning of a video compilation on YouTube at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l9a3c1JiuWQ, or anywhere else on the INTERNET.

It appears Mr. Gampper does not want anyone to see the photo of the Wingfoot Air Express airship until Jan, 2032, the 70th anniversary of his grandfather's death when the photo enters public domain. <sigh>. I assure you, my readers that I would have been quite happy to cite Mr. Gampper or the Gampper family as the copyright owner of the photograph. Unfortunately, the terse nature of the email left be with only a bitter taste in my mouth, due to that fact that apparently the Gampper family wants nothing to do with this tragic history, even though their ancestor did nothing wrong.