This interesting airship never flew. It was the brainchild of Thomas B. Slate, the same Slate who amassed a fortune when he invented a commercial process for making and marketing dry-ice. Slate started and was co-owner of "Prest Air Devices" in 1923. The company was sold to DryIce Corporation of America in 1925 and Slate took his fortune to Glendale, California to pursue his dream: Build his innovative, all-metal airship and create a commercial airship transport company. He stared to work and in 1924 incorporated as "Slate Aircraft Corporation".

Construction

The design of Slate's airship was revolutionary and construction began almost immediately after Slate secured land at the Glendale Airport (which eventually became the Grand Central Air Terminal.) Among the innovations in his design: A light-weight, gas-tight, all metal envelope containing no interior ballonetes; a steam powered "vacuum" propulsion system (!); an elongated, tear-drop shaped hull to aid the vacuum propulsion; no need to dock or moor - instead passengers would be lowered to the ground by a unique elevator system.

The unconventional design used thin-wall tubing of duralumin forming a frame of ribs (18 thousandths-inch thick tubular dualumin), and strips of ultra-thin duralumin sheets (12 thousandths-inch thick dualumin) formed into gores with a corrugated pattern right at the construction site using a large stretch-and-form press then seamed together using a crimp seam similar to the way a lid is crimped to a tin can making an air and liquid-tight seal. Each corrugated gore was riveted to the underlying ribs. The corrugation was intended to allow the metal hull to expand and contract with interior pressure and temperature changes while retaining a gas-tight seal. All the duralumin was manufactured in Germany and imported. In the next two photos, you can get an idea how the frame was assembled.

Photo credit: offbeatoregon.com

A great trench was cut into the earth to make room for the emerging airship frame and as the hull was assembled. The frame was suspended in a sling permitting it to be rotated as needed to keep the successive attachment of the longitudinal gores at the same work height. The result of the construction was a monocoque, very strong frame.

Photo credit: UCLA Library

Unfortunately, the famous Santa Ana winds of California twice damaged or destroyed the fragile frame more than once, so Slate was forced to accelerate the construction of a shelter over the assembly.

Photo credit: offbeatoregon.com

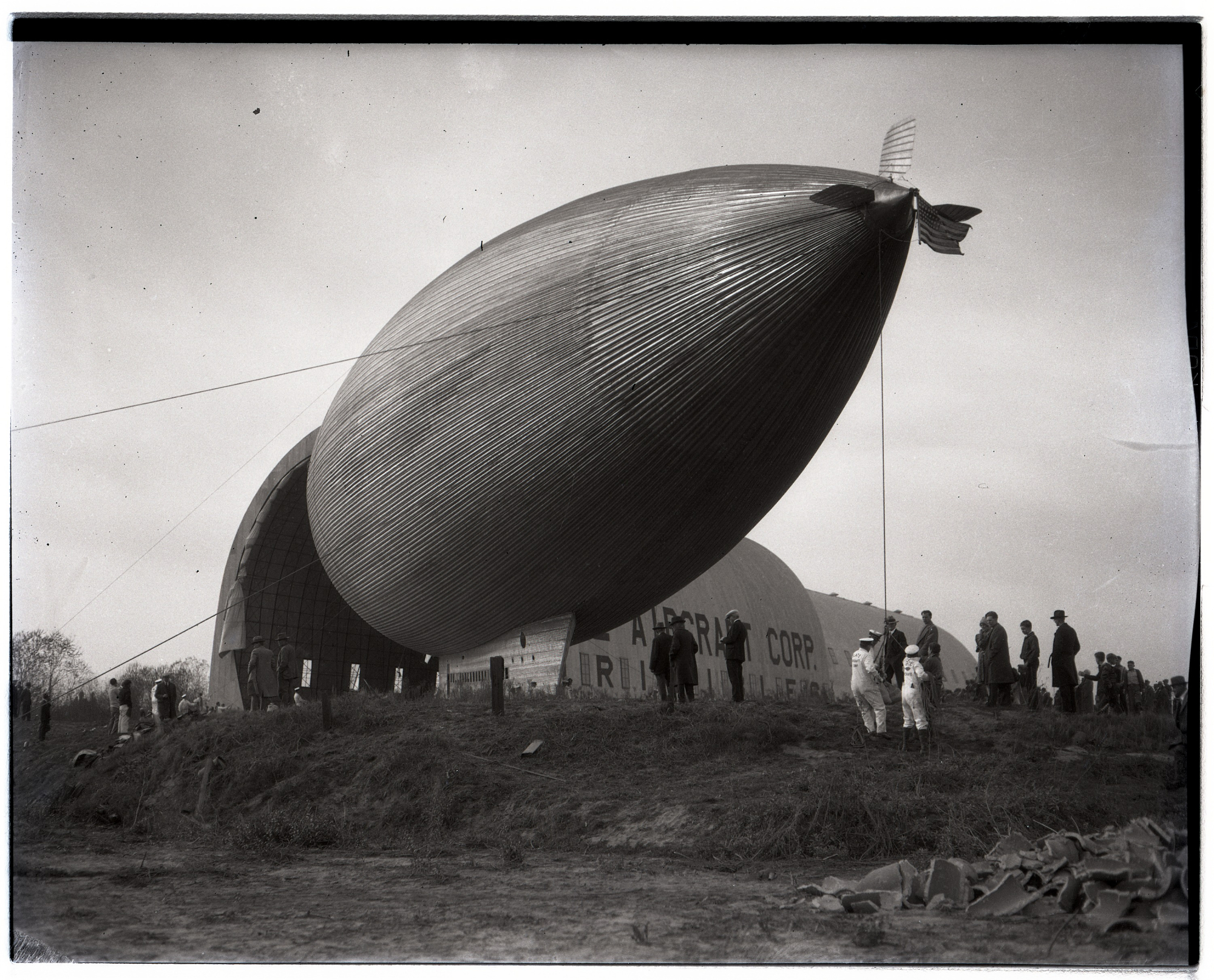

The completed airship, minus its steam powerplant, was brought out for display to the press on 6 or 7 Jan 1929. (Available reports are inconclusive as to the exact day.) From Wikipedia: The airship was "first brought outside on 6 January 1929. With a crowd watching, Slate's handlers released its restraining cables until the shiny unit rose to thirty feet above the concrete. The initial public appearance was an unmitigated success. However, problems with the steam-production equipment delayed flight testing until December, when Slate gave up on that system and installed an internal-combustion engine (a Wright Whirlwind) driving a conventional propeller to move the craft."

Photo credit: vintageairphotos.blogspot.com

The photo above is likely from the January 6 or 7, 1929 demonstration for the public and press. It is tethered to the ground. The steam powerplant was not yet installed at this time, so while the airship was filled with hydrogen, it did not require a full pressurization of hydrogen to compensate for the weight of the airship frame to permit the airship to become buoyant. Note the small area of the tail surfaces, the rudder and elevators. It was expected that large tail surfaces would not be required due to the proposed method of propulsion. More on this later. At the time of this photo, there were no steam turbines installed to drive propellers on either side of the forward cabin as available literature suggests were intended by design. Later, after abandoning the steam power idea, Slate added a conventional engine and propeller to the aft of the passenger compartment to compensate for the air resistance imparted by the passenger compartment which was an impediment to the air flow around the asymmetric envelope. This added engine is seen mounted at the aft of the crew compartment in the later photos of the airship from December, 1929. (Also visible in the later photos are the two, small side engines/propellers and enlarged tail surfaces):

Photo credit: vintageairphotos.blogspot.com

Throughout 1929 the City of Glendale was brought out of the hanger for static tests. Photos of these "showings", though well-attended by the public and press, have not been found. It would be interesting to see the small changes made as the project evolved.

One of the greatest prizes in research like this is to find a high-resolution photo. I found one such photo of the City of Glendale, provided here from the Smithsonian. It's a beauty. Click on the photo below and behold the full-sized scan. Unfortunately, it is undated, only identified as "circa 1928-1929". The photo is early 1929 because by December that year, the "drop off" in front of the hangar door had been bull-dozed, filled, and leveled.

Photo credit: Smithsonian

An Elevator?

Slate proposed a novel method of disembarking passengers such that the airship would not have to land or be moored. Passengers would be lowered to the the ground or to the top of buildings via an elevator. The ideas was that the pilot would steer the airship into the wind, powering the forward blower just enough to keep the airship stationary. The airship's reserve fuel tank would first be lowered to the ground becoming an "anchor". Then the elevator would be lowered via a second cable, held captive from rotating by an arm which would follow the other cable. (See illustration.)

Photo credit: offbeatoregon.com

Slate's bizzare method of Propulsion

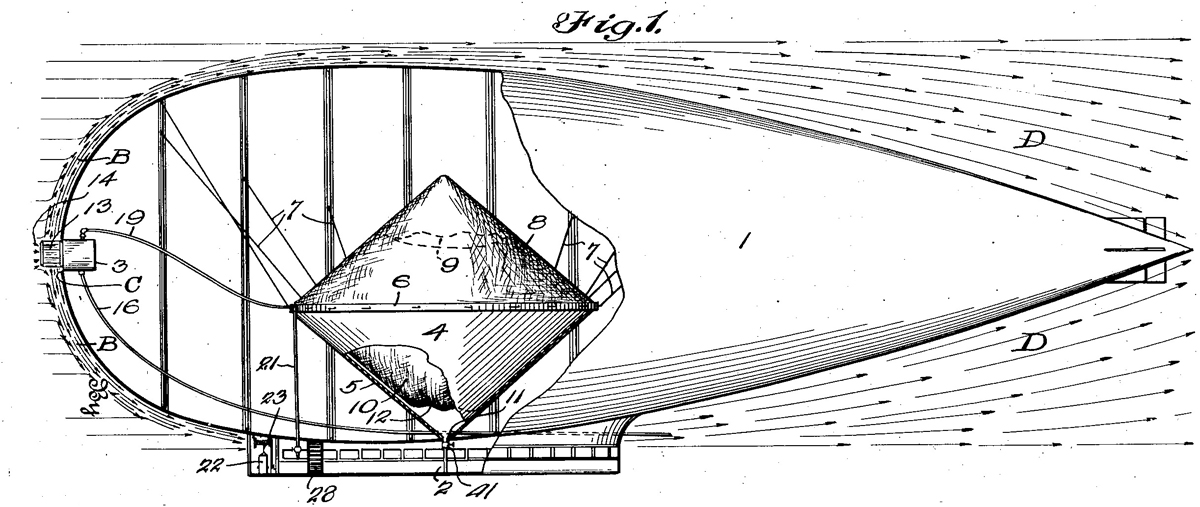

A Feb, 1929 article in Flight magazine describes the propulsion system this way: "In the Slate dirigible, the power system consists of a generating plant comprising a high-pressure flash-type 'boiler' made up into two to four units, with condenser. Only 5 gals. of water are used in the entire plant, which gives about 600 lbs./sq. in. pressure, and it is. stated that but 1 gal. of water is consumed for every 1,000 miles of travel. The entire power plant is divided into seven units, comprising that number of steam turbines of various sizes, giving a total of about 600 h.p. The main turbine, of 400 h.p., is connected directly to a centrifugal 'blower' mounted in the nose of the hull, and is supplied with steam from a generator in the cabin. We will explain the purpose of this blower presently. Two other power units, each developing about 40 h.p., are mounted one on each side of the cabin, at the forward end, and drive ordinary airscrews. The other turbines include two of about 10-h.p. for operating cargo, etc., elevator hoists ; one of 8 h.p. for operating electric generator for wireless, lighting, etc.; and one supplying power for, we understand, the operation of the generating plant (water pumps, etc.). The total weight per horse power of the entire plant comes out at about 3 lbs."

"We now come to the novel method of propulsion employed in the Slate airship, which is as follows : the 'blower' in the nose, previously mentioned, and which is 4 ft. 10 in. diameter, draws in air from the front of the airship and throws it back along the surface of the hull. A partial vacuum is thereby created ahead, inducing a suction effect on the airship, while the air-stream flowing backwards gives rise to a positive pressure at the rear, which drives the airship forward. The air stream also assists the effective operation of the tail control surfaces".

"The blower rotates at a speed of 4,000 to 6,000 r.p.m., and the air stream produced is stated to have a velocity of about 300 m.p.h. The two airscrews on the cabin are primarily intended to offset the parasite resistance of the cabin. They are, however, reversible and can be used to check the forward motion of the airship, assist in turning, or holding the airship stationary. The cruising speed of the ship is estimated at 80 m.p.h."

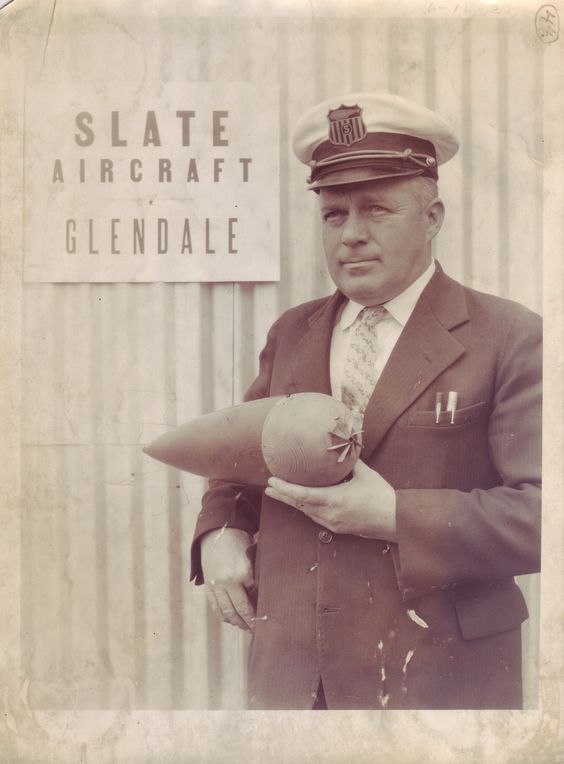

Slate's "blower" at the nose is seen here in this June, 1928 photo of Slate himself holding a model of his invention:

Photo credit: Public domain

You get an idea of Slate's thinking in this illustration from his patent. The "blower" or fan or impeller at the nose is supposed to suck-in air from forward of the airship, creating a partial vacuum which would (theoretically) be filled as the airship moved forward into the partial vacuum. At the same time, the blower or fan was expected to move a large volume of air over the nose of the airship and that air would "hug" the form of the airship all the way to the tail. It was thought that this flow of air near the surface of the envelope would permit the use of smaller tail surfaces. This explains why the rudder and elevators of the City of Glendale are so small compared to all other airships of the early 20th Century.

Photo credit: vintageairphotos.blogspot.com

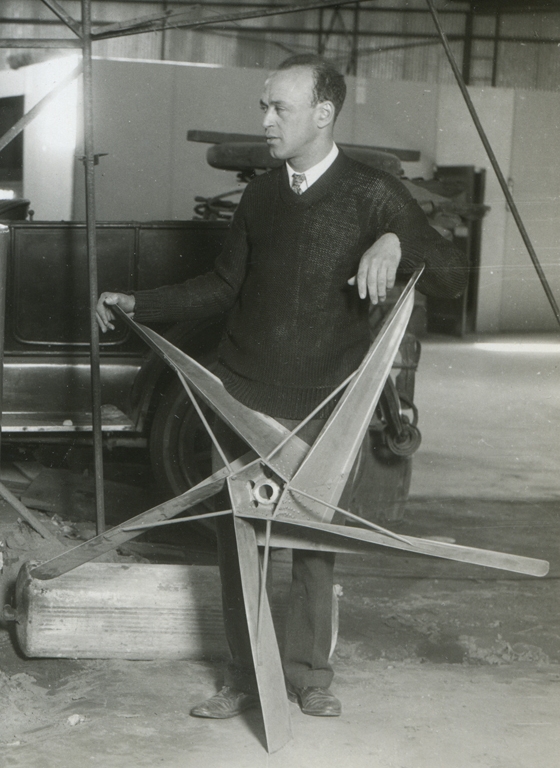

Compare the next two photos. The first is a close-up and enhanced photo of the nose of the City of Glendale showing the blower. One can see that the blower/fan was mounted as closely to the surface of the envelope as practical. The second shot shows the blower/fan held by engineer L.R. Hawkins, providing some scale.

Photo credit: vintageairphotos.blogspot.com

Photo credit: vintageairphotos.blogspot.com

After the "photo op" in January, 1929, trouble ensued. Slate's steam engine was not working out and ultimately over the course of 10 months from January to December 1929 he redesigned his propulsion system using an aviation engine. He installed a Wright Whirlwind aircooled, radial aircraft engine. This engine dramatically altered the initial design, moving the blower/fan/impeler significantly farther from the surface of the airship's nose. When the airship was brought out again in December, 1929 for test flights, you can see this new engine in the photos along with the larger tail surfaces and the aft engine on the passenger car:

Photo credit: adapted from vintageairphotos.blogspot.com

The last photo (above) was the final configuration of the City of Glendale as it was prepared for test flights. It was taken between the 17th and 21st of December, 1929. Accounts as to the exact date vary.

Specifications:

- Length: 212 ft (64.6 m)

- Max Diameter: max 58 ft (17.7 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 3.65

- Tubular "ribs": 1/18,000" thick tubular dualumin

- Envelope: 1/12,000" thick sheets of dualumin, formed into strong corrugated, longitudinal strips attached all the way around the hull.

- Hydrogen/Helium Capacity: 300,000 cu ft.

- Weight/lift: About 14,000 lbs/usefull lift reportedly about 7,000 to 10,500 lbs.

- Speed: Advertised 80 mph, top 100 mph. (Never demonstrated).

- Passengers/Crew: 35/5.

- Operating dates: Never Operational. Exposure to the sun in Dec, 1929 while filled with hydrogen led to failure of the envelope, and it was condemned and not repaired.

- Visual: Extreme teardrop shaped, clearly corrugated skin, small tail surfaces, no typical engine nacelles, engines or propellers. Tiny fan affixed to the nose. Long, rigid passenger and crew cabin affixed to the bottom of the envelope.

Operations

It's a bit hard to describe "operations" of the City of Glendale since the fanciful airship never flew! But we can take a look at its last days...

The record is sketchy, but it appears that on 17 December, 1929, after refitting the airship with the radial aviation engine and larger tail surfaces, the airship was brought out apparently for its maiden flight. It was an unseasonably warm day for Southern CA, and it was not long after the airship was exposed to the sun that the hydrogen, heated by the sun, expanded. Emergency relief valves activated to release the building pressure.

On 19 December the City of Glendale was once again moved out of the hangar, this time with its engines running. But within a few minutes the sun had again heated the hydrogen. This time, it appears the emergency relief valves had been left on "manual" and did not open to relieve pressure. The "pop" of rivets was soon heard over and over and was followed by an explosion (apparently as one or more seams gave way. The port side had failed, appeared distended, the duralumin gores bulging.

The airship had to be towed back into the hanger, the maiden flight indefinitely postponed. Initially, Slate reported that the repairs would only take a few months but later it became clear that the envelope was a total loss. A grave engineering mistake had been realized. No failure of this manner had been anticipated. A repair meant a complete rework. But the time was December, 1929 and the Stock Market had crashed in October. Slate's investors dried up and so did his aviation company.

Demise

On that fateful 19 December, the City of Glendale was moved back into the hangar, never to emerge again. After two years of trying to find investors Slate filed for bankruptcy in 1931. The City of Glendale sat suspended in the hangar, gathering dust.

Ignominious End

Sometime in 1931, admitting complete defeat, in a final grand "show" in front of the press, Slate himself initiated collapse of the envelope of the unpressurized City of Glendale by dropping a 50 pound bag of sand on it from a catwalk above the airship. Without the supporting internal pressure, the envelope immediately folded. The airship and the hangars were subsequently disassembled and sold for scrap. The Slate Aircraft Corporation ceased to exist.

Sites of Interest

Glendale, California

The Slate Aircraft Corporation and the airship "City of Glendale" are known to have been at the Glendale airport, which later became widely known as Glendale's "Grand Central Air Terminal". So the question is: "Exactly where was the hangar?"

Turns out there are several aerial photos of the airport, which include the Slate hangar! Here is one:

Photo credit: http://members.tripod.com/airfields_freeman/CA/Airfields_CA_LA_C.htm#grandcentral

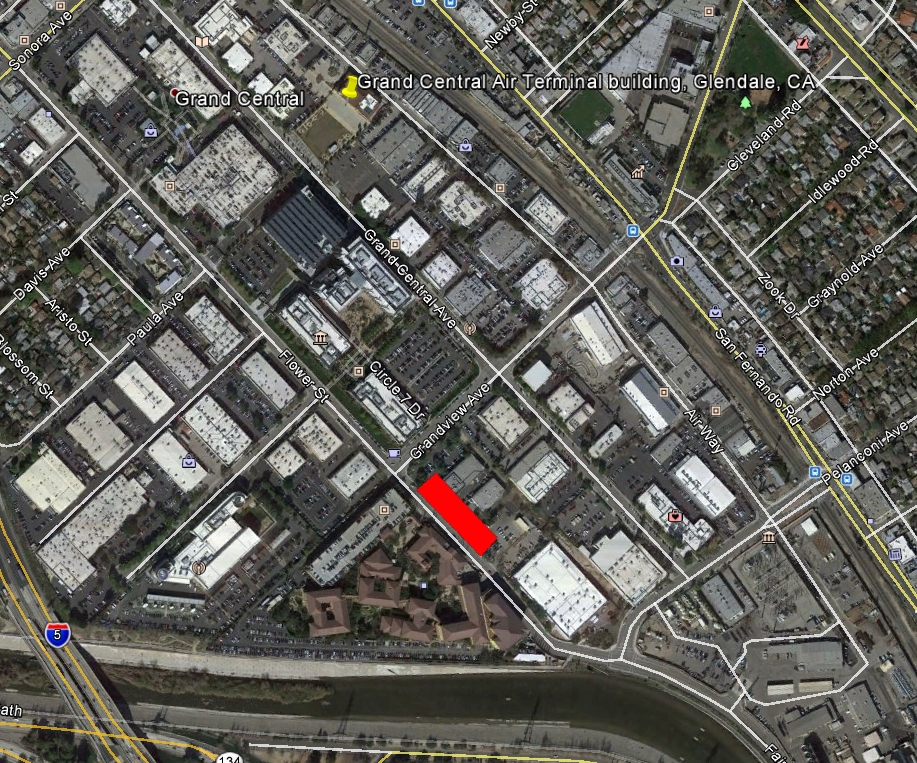

This photo is a gold-mine because not only is the hangar present (with the City of Glendale airship snug in the hangar, but also visible is the famous Glendale Air Terminal building which still exists today and a couple of other structures still present today! This one photo actually permits a fairly precise identification of the former location of the Slate hanger. And here it is:

Photo credit: Google Earth

The hangar was likely located at what is today the NE corner of Flower St and Grandview Ave.

The location of red rectangle in the photo above, representing the location of the hangar is at (Lat Lon) 34.158323 -118.284758, found here in Goole Maps:

Hope you enjoyed discovering this lost history of the City of Glendale airship and finding where it was built, housed, and enjoyed a brief existence.