Barton-Rawson Airship

(The Barton Airship was renamed in July, 1905 as the Barton-Rawson Airship. The terms "Barton" and "Barton-Rawson" are used interchangeably in this article.)

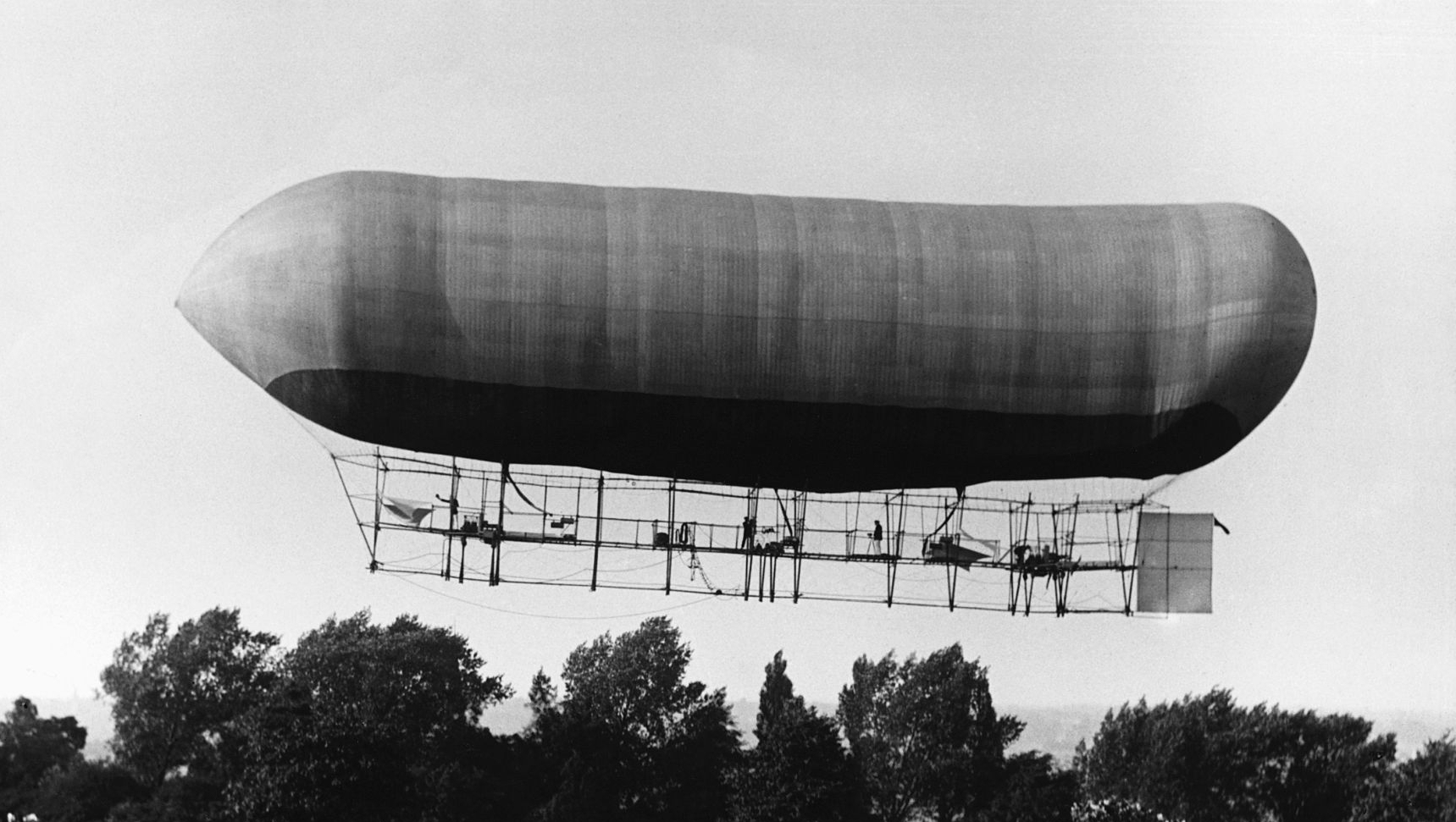

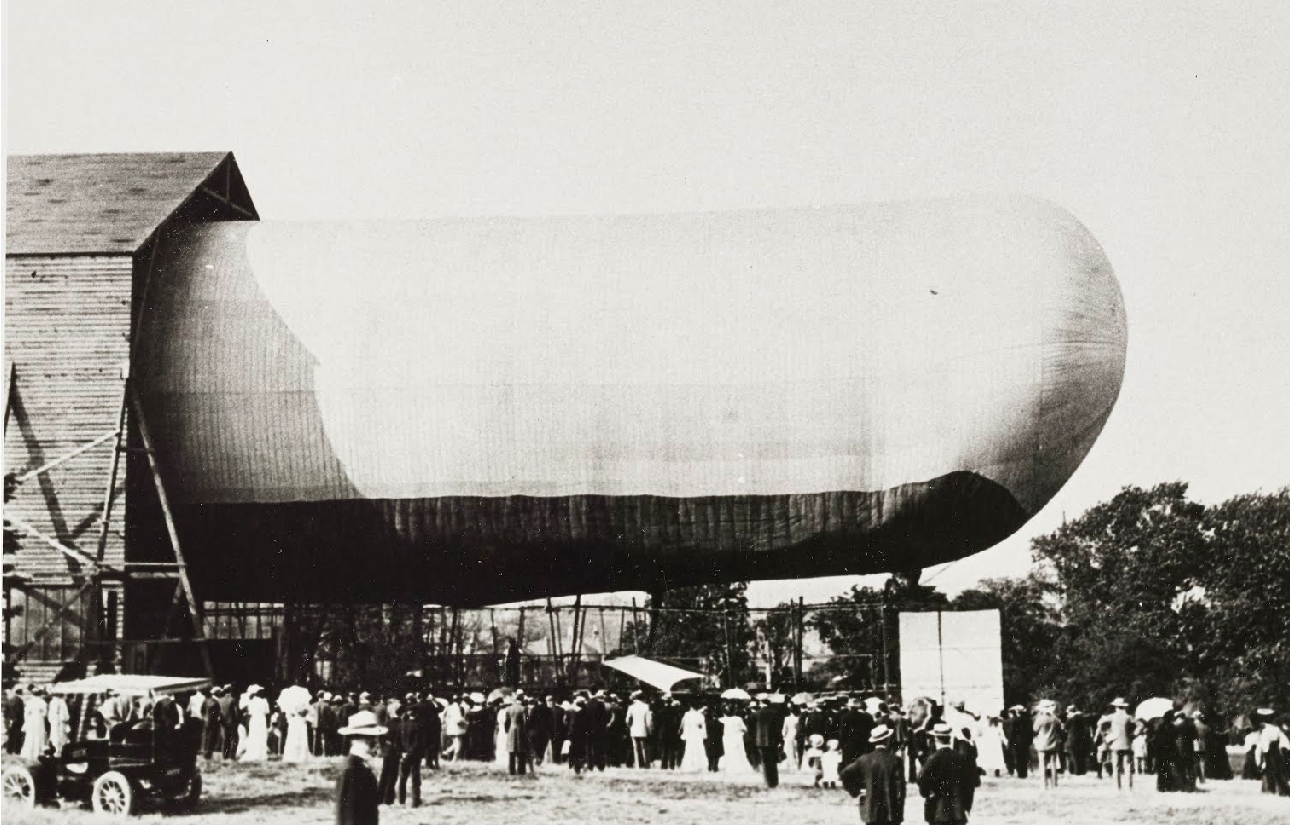

The Barton-Rawson airship on its 2nd and final flight, July 22, 1905

Photo Credit: Public Domain

This was one of the most difficult airship research projects I have encountered. It was difficult because the airship was constructed in relative secrecy making it exceptionally hard to ferret out solid details of it and there are few high-quality photos. Even though Dr. Francis Alexander Barton, a general practitioner in Beckenham, Kent, UK was well-known in aviation at the time from a long record in ballooning as far back as 1883 (including an 1899 patent for "An improved aerial machine or airship"); and was even a member, and President, of the Aeronautical Institute and Club of London; AND there are many citations in the available sources of the era - only very "general" details seem to be available.

In early 1901, the British War Office solicited a builder for a practical airborne craft. (I do not have the details of this solicitation though I would like to find it!) Dr. Barton apparently proposed an airship, a cross between an winged, heavier-than-air aircraft and a dirigible, lighter-than-air aircraft, and was awarded the contract. (Barton was a vocal proponent of employing lifting surfaces (called "aeroplanes" in those days - actually segments of "wings") combined with a balloon. The aeroplanes would provide sufficient lift when the airship began forward motion.) Source: English Mechanic and World of Science, No. 2050, July 8, 1904, page 497.)

Barton was not President of the Aeronautical Institute and Club until June, 1902, and did not even incorporate his airship company, "Barton Airship Syndicate (Limited)" until 1903, and there is much I have not identified about Barton in the early years to explain how he won a 1901 government contract. (Sources: Flying magazine, June 1902, page 144 and The Automotor Journal, February, 14, 1903, pg 188.)

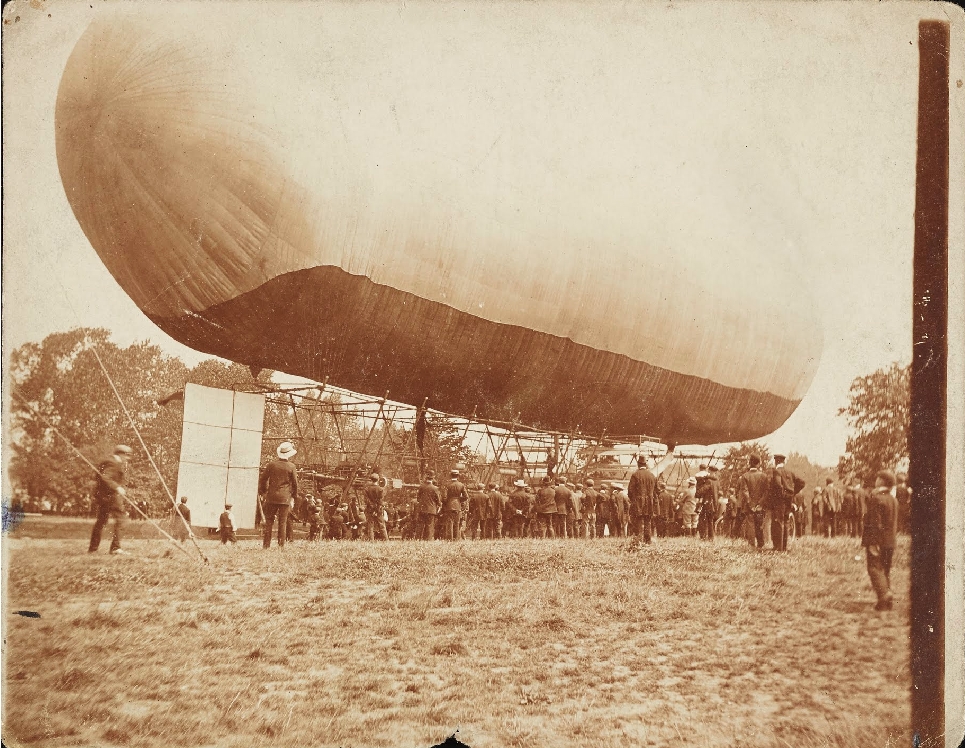

The Barton-Rawson Airship on July 22, 1905 ready for its public demonstration.

Photo Credit: Public Domain.

Construction

Equally shrouded in mystery is the construction of Barton's airship. Upon award of the British War Office contract, Barton apparently refused a government site at Fort Clarence in Chatham/Rochester, UK, to build his airship (about 28 miles ESE of central London) and arranged instead for a site on the grounds of the Alexandra Palace about 6 miles north of central London. (Source: Hornsey Historical Society.) It is possible the Alexandra Palace site was considered mutually beneficial as Dr. Barton was self-funding his airship, and the palace officials paid him to build his airship shed on the grounds and the palace would benefit by attracting more visitors which already had balloon and parachute demonstrations ongoing.

The design of the airship slowly evolved as Dr. Barton experimented with his aeroplane and propulsion ideas. In his role as a leading aviation aficionado in London, he knew many of the other aviation experts of the time and listened to ideas and presented his ideas at meetings of the Aeronautical Institute and Club - some well received, others not so much. There are articles in engineering, aviation and automotive magazines of the time which reported quite a number of design changes over time. The article on "Aerial Navigation" by Octave Chanute in the 1903 Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution declares: "The balloon of Doctor Barton might gain this speed [25 mph] if it were not 40 feet in diameter, besides being loaded down with aeroplanes, and it remains to be seen what will be the effect of this combination."

The shed and hydrogen generating plant were likely built in early 1902, though the exact date is unknown. Barton, who was still making design changes continued to make slow progress as he tested his ideas. A report in the May 3, 1902 Scientific American, page 308, described only the plans to date for the airship and referred to a model, but concluded that "The government trials are to be carried out in the course of the next two or three months." (That would have been in July or August, 1902.)

But the contract Barton had with the War Department ended in August, 1903 and the airship still had not flown. Without any prospect of selling his airship to the government, I suspect Barton was forced to slow his progress even further since he was still self-funding the project.

By the time the airship was ready to fly, Barton's design partner and engineer, Frederick L. Rawson had been provided the honor of being added to the ship's name which became the "Barton-Rawson" airship.

Here are the specifications of the as-built Barton-Rawson, as best as could be determined by available sources:

Specifications:

- Length: 180 ft (55 m)

- Max Diameter: max 41 ft (12.5 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 4.4

- Envelope: Varnished Japanese Silk. 3 interior hydrogen compartments and a ballonet. Hydrogen pressure in the 3 compartments could be controlled via proprietary valves

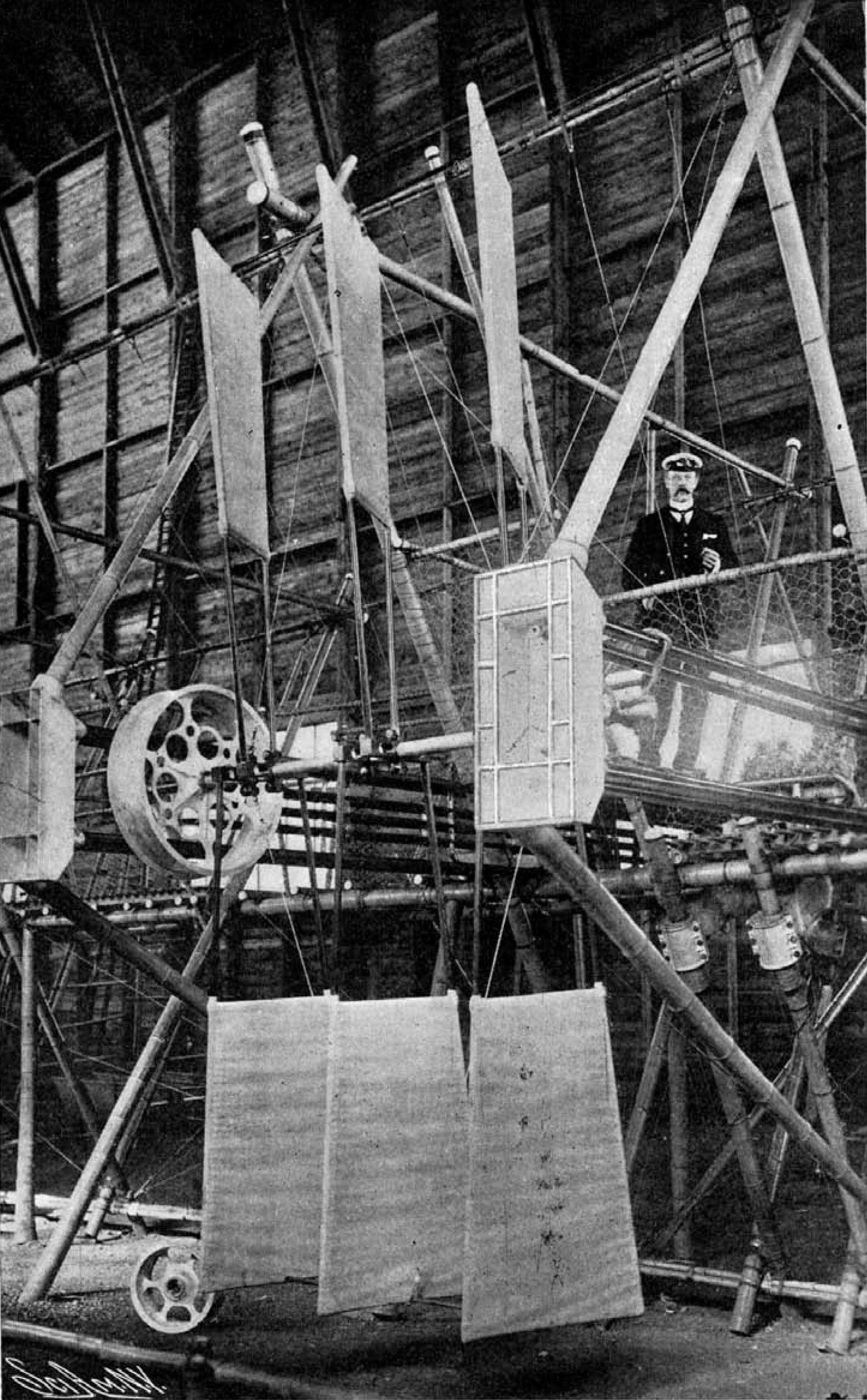

- Power: Originally, three, 50 HP engines driving 6 sets of propellers, 3 on each side of the keel. Each propeller was 17 feet in diameter and 3 stacked blades each ("Triple Mangin" type) operating at 140-200 rpm. By July, 1905, the midship engine was abandoned, and the remaining propellers, now four, were reduced to 7 feet in diameter but operating at 1000 rpm

- Gas Capacity: About 200,000 cubic feet of hydrogen

- Speed: Unknown. Anticipated 20 mph (Never demonstrated)

- Passengers/Crew: (Proposed) Crew of seven: three engineers, helmsman, aeronaut, balancing-pump engineer, and captain

- Operating dates: Never fully operational. Flew first on July 19, 1905, then publicly on July 22, 1905. The July 22 flight did not end well

- Visual: Conventional airship design except for the larger keel in proportion to the gas envelope which also contained "aeroplanes" (basically wing segments) between the bottom of the gas envelope and the keel intended to provide lift when the airship was driven forward by its engines and propellers

The Barton Airship triple propeller system as the development progressed in 1903.

These were abandoned for a new design by 1905.

Photo Credit: Scientific American, Jan 16, 1904, pg 44.

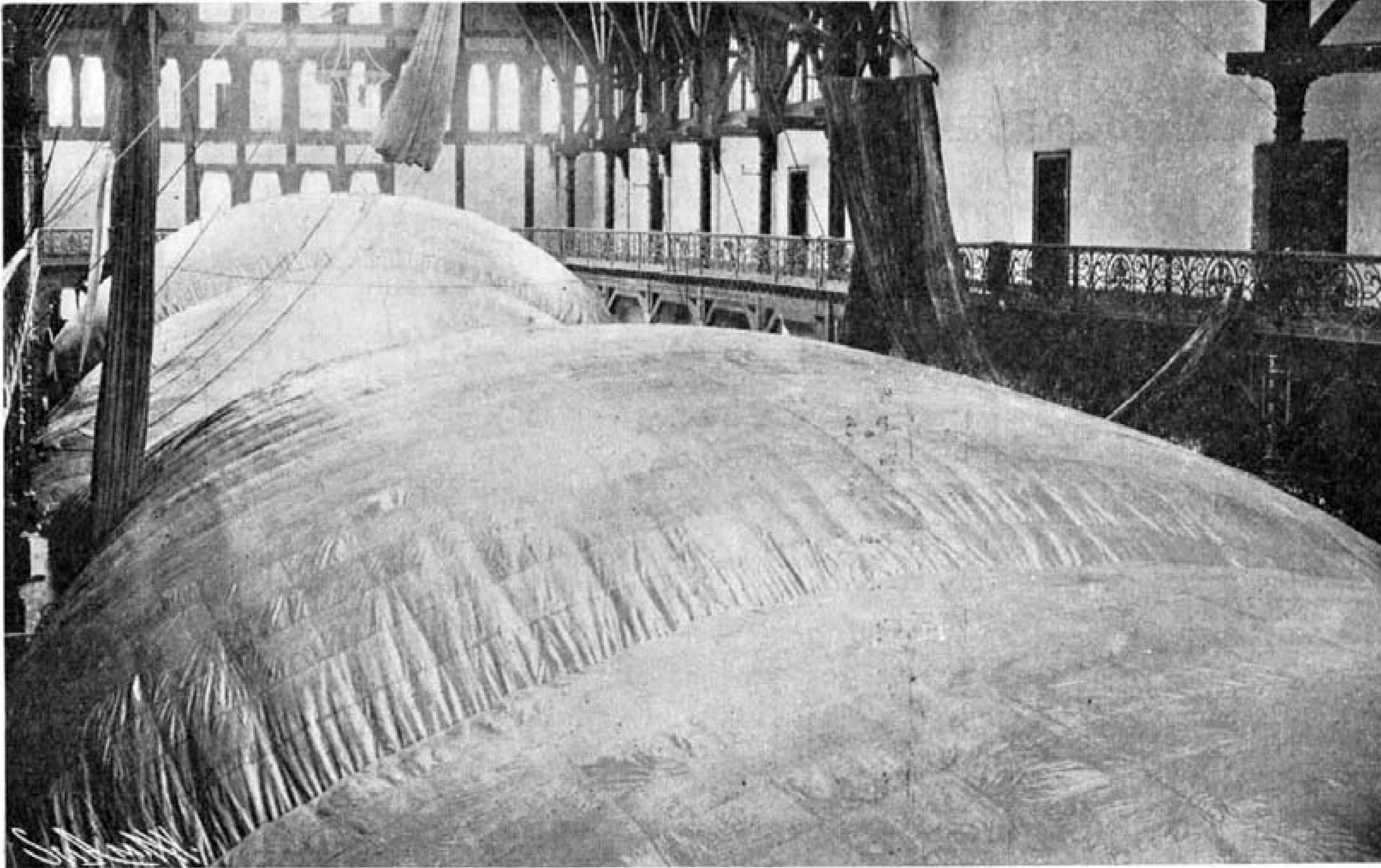

The enormous envelope of the airship's hydrogen gas bag was, according to the Jan 16, 1904, Scientific American, page 44, assembled in (what was then) the "Alexandra banqueting hall". Thus the airship shed itself was used to design and construct the keel and presumably to conduct experiments toward the final design.

Barton Airship envelop testing in the Alexandra Palace Banquet Hall.

Photo Credit: Scientific American, Jan 16, 1904, pg 44.

Operations

"Operations" were never achieved. What was achieved were two flights in July 1905, the 2nd ending in utter failure, but with no fatalities.

By the time the airship was ready to fly, several modifications had been made in the airship's configuration since development had begun in 1902. When brought out of the shed on 19 July, 1905, the airship was clearly missing most of it's 30 aeroplanes. There are only two photos I've located, one reproduced here, which shows the airship in its 19 July configuration. (The 2nd photo could not be used as it is shamefully watermarked by Getty Images.):

Barton Airship on 19 July, 1905.

Photo Credit: Public domain.

In this photo, immediately above, one can see at most 6 aeroplanes, and the mid-keel third engine seems to be present (given the presence of an apparent gas tank.) The aft engine may be running as the aft, starboard propeller seems to be turning (blurred during exposure). It is likely that the propellers at this time had already been changed to the 7 ft diameter wooden version. The configuration seen in this photo, nevertheless, is clearly not the configuration seen on the 22nd of July. (See next photo).

(Also in this photo, above, we see evidence that the airship was brought out of the shed nose-first since support cables from the front of the shed are visible in the photo. Note also that the flight of 19 July was unannounced, so the onlookers in the gathering crowd were guests or visitors to the Alexandria Palace that day.)

With weight-saving measures, which were already estimated to be needed, the craft was made ready. Jul 19, 1905 was a Wednesday and the ship was brought out for its unannounced test-flight. The flight was reported to have been completed without incident and the airship was made to complete a circuit of the Alexandra Palace grounds.

Upon completion of the flight, Dr. Barton apparently decided the craft was ready to demonstrate publicly. The date was set for Saturday, 22 July and a gala planned.

When the airship was brought out of the shed on that Saturday, the general appearance was the same but the triple propellers on each side of the keel had been replaced with single propellers of wood which were 7 ft in diameter, rotating at 1000 rpm, verses the original 140-200 rpm of the "Triple Mangin" design as seen in the photo above. Clutches had been eliminated and the reduction gear between the 50 hp engines and the propellers had also been abandoned, and the engines drove the propellers directly by belts. The original three, 50 hp engines, were reduced to two. The original 30 "aeroplanes" were also now gone on account of weight. The aeroplanes had been replaced with four wing structures of canvas, two forward and two aft, which, reporters cautioned, seemed insubstantial to have provided any merit to the airship.

Level flight had, all along, been intended to be maintained by an innovative balance system of two water tanks, one forward and one aft, and a pumping and valve system to transfer water from one tank to the other. By the time of the 22 July flight, the aging envelope and hydrogen gas, now contaminated by having been in the envelope too long meant even more weight had to be eliminated so even this water-tank-leveling system had been abandoned.

The Barton-Rawson Airship coming out of its hangar, on July 22, 1905 given the crowd viewing the emergence.

Photo Credit: Public Domain.

(Note in the photo above, the airship is emerging from the shed tail-first. Evidently, upon completion of the 19 July test flight, the craft was ingressed nose first.)

On that Saturday, preparations included the elimination of (an additional?) 300 pounds of ballast, two members of the crew, and the remaining original aeroplanes - replacing them, as mentioned, with only 4-outboard "wings" of canvas. Five men made up the crew: Dr. Barton; Mr. A. E. Gaudron, who had charge of the gas valves and ballonet of the aerostat; Mr. Rawson, engineer, at the helm; and Mr. Henry Spencer, forward engine; and Mr. Newton, aft engine.

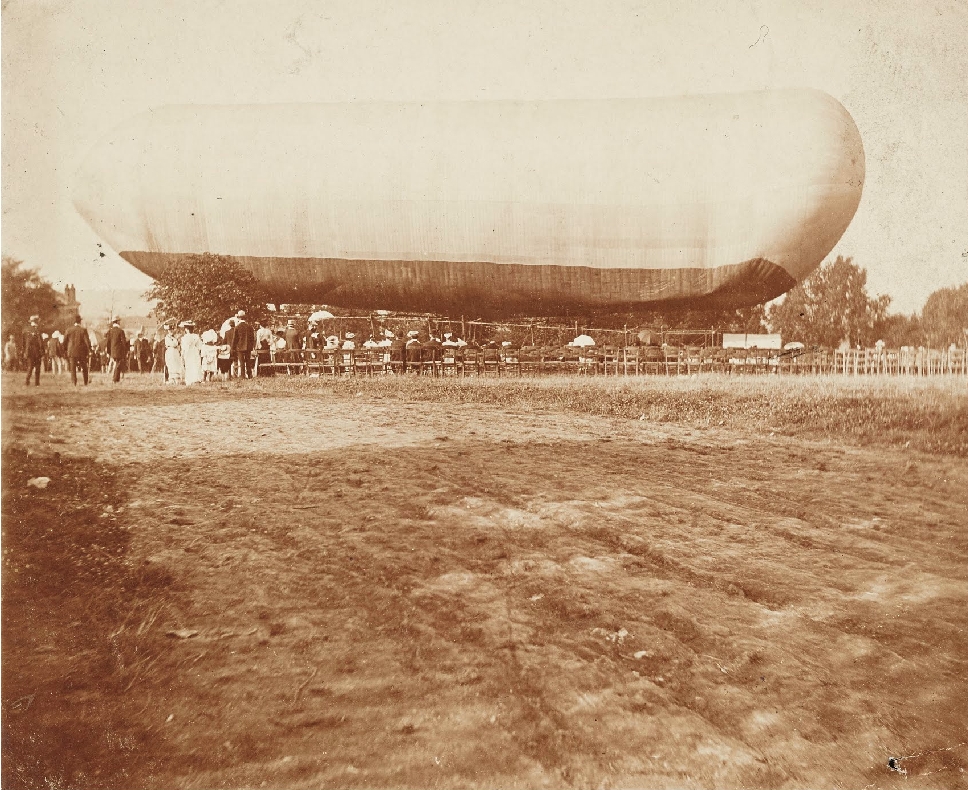

The Barton Airship on July 22, 1905.

Photo Credit: Public Domain.

(A close examination of this photo shows a large number of chairs set up for guests and visitors.)

Demise

Summary of the ill-fated flight

It was breezy that Saturday, possibly 20-25 mph winds, and flight preparations along with a social event held in the Hangar in advance of the airship being withdrawn from the shed delayed the flight till the late afternoon. After some difficulty extracting the craft from the shed due to the airship's enormous volume, and despite a trench having been dug to permit the lower edge of the keel to not contact the ground, the craft was made ready about 5 pm.

Preparations complete, the craft was pushed off at about 5:30 pm, and the forward and aft engines both started. Upon ascending, and drifting in the breeze, Mr. Rawson, in command, gave the order to steer about to face the wind. The airship continued to climb, and at about 500 feet altitude, it became evident to both the crew and the spectators that the craft could make no headway against the wind, not even hold her own. They gave up, and steered the craft around with the wind and let her go a while, still rising, before they steered around into the wind again for another try. There are reports that each time she tried to face the wind, the nose of the envelope would crumple a bit!

Barton Airship ascending after launch, 22 July, 1905.

Photo Credit: Public domain.

Soon, the effort to dominate the wind was abandoned and after attempting to return to the starting point, it was evident that also could not be achieved, the airship, and her crew, drifted east. They attempted to keep the ship broadside to the wind, perhaps to find a lesser strength pocket of wind, but soon the ship drifted out of sight from the Alexandra Palace grounds.

Barton Airship adrift after fighting the wind..

Photo Credit: Public domain.

A "plucky and adventurous achievement"

Continuing the story now verbatim from the Jul 29, 1929 Automotor Journal, pg 934:

"At one time descending, but soon after rising in the air till an altitude of about 2,400 feet or thereabouts was reached, the airship gradually approached Romford, in Essex, where she was ultimately brought down with great success by M. Gaudron in a potato field near Heaton Grange. A garden party was in progress at the Grange, and the sudden descent of the airship upon the scene provided an [unexpected] diversion for the guests, of which they were not slow to take advantage. The airship was quickly surrounded, and Dr. Barton, who was in the bow, was immediately the centre of an admiring throng of ladies, who heartily and even enthusiastically showered upon him feminine congratulations on his plucky and adventurous achievement.

"And that was the cause of the trouble. Both Mr. Rawson and M. Gaudron were conscious that they too had bravely 'adventured' as much as Dr. Barton, and forward they moved to join him at the bow and to share in the congratulations. The balance of the airship was upset. The rear portion began to rise up, and the gas tending to accumulate at the highest portion of the gas-vessel increased the mischief. In fact, the airship was proceeding to stand upon her head, and in this way to eject Dr. Barton and Messrs. Rawson and Gaudron into the centre of their admirers, Mr. Spencer alone being left in the stern, and in danger of soaring away with the liberated airship into the blue beyond. Without wasting an instant, Mr. Spencer, with great presence of mind, grasped the 'ripping-gear,' and tore up the gas-vessel, the hydrogen issuing from the rent balloon with a roar. Down came the airship, the gas-vessel, of course, completely wrecked, the frame a good deal damaged, but the motors alone escaping without injury. The adventurous experimenters ultimately extricated themselves from the debris, and were so much elated at finding themselves safe and sound that they hardly felt the destruction of their airship. In fact, it is satisfactory to learn that Dr. Barton did not intend using the airship further even had she completely escaped injury."

Needless to say, the Barton-Rawson airship was no more, and though Dr. Barton boasted of building another airship, capitalizing on the lessons learned with this craft, Dr. Barton was finished building airships, turning his thoughts to heavier-than-air airplanes of which he did build one, unpowered prototype, a twin-floatplane of bamboo - unpowered because of the unavailability of a light-weight engine. The airplane was tested by towing it behind a motorboat, but it was wrecked during a trial on Sep 26, 1905. Out of money, he turned his thoughts to other ventures.

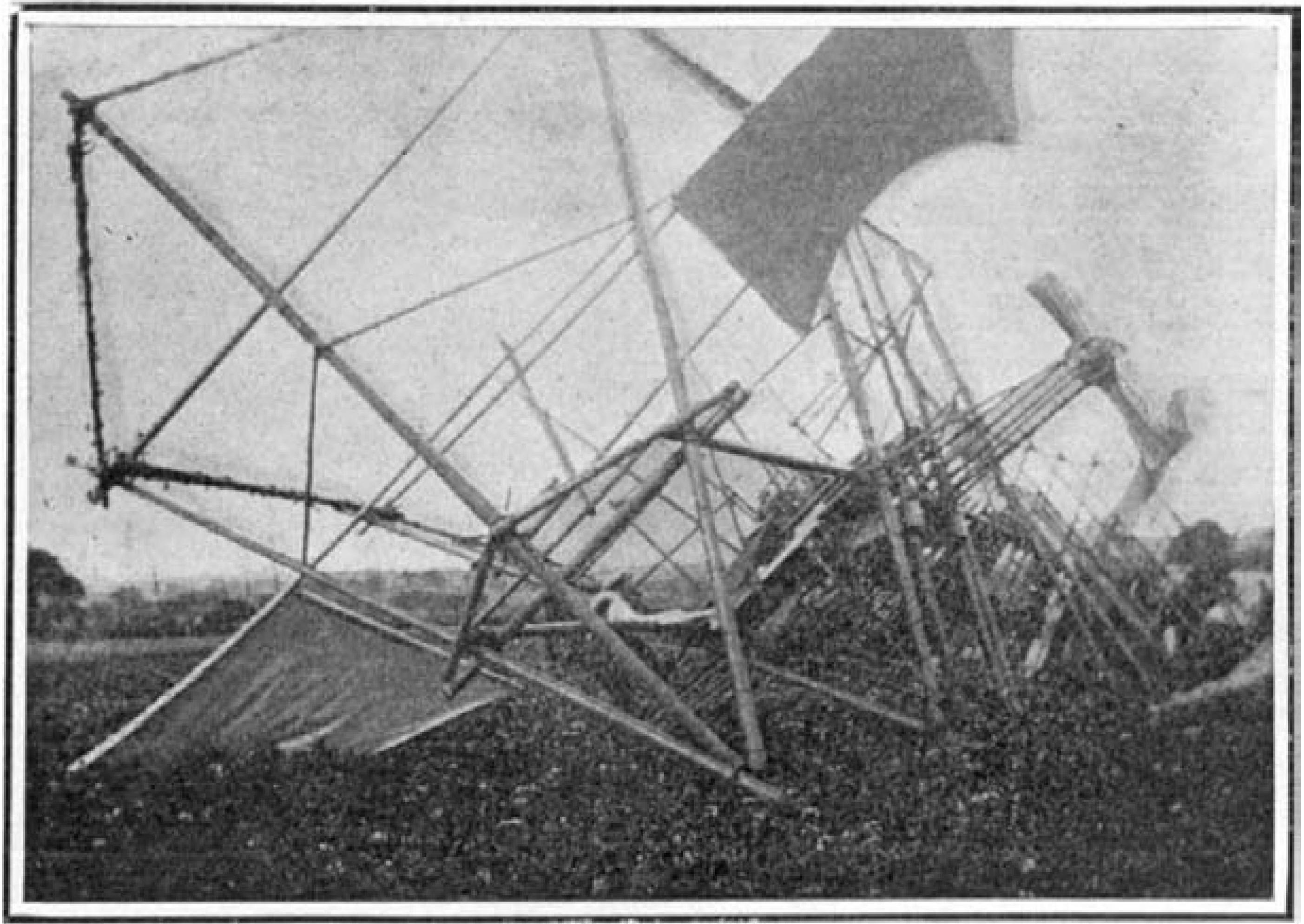

Ignominious end

When Mr. Spencer pulled the ripping valve, a huge rent was opened in the envelope and the hydrogen, it is reported, was "liberated with a roar". An article in the Sep 9, 1905 Scientific American magazine reported that the gas envelope was ripped completely in halves and the framework collapsed rapidly to the ground. No one was injured, and the keel, owing to the flexibility of the bamboo frame, suffered only minor damage.

Only the two engines were saved, and the bamboo framework was abandoned and used by locals for firewood.

Barton' wrecked Airship. Photo Credit: Scientific American, Sep 9, 1905, page 196.

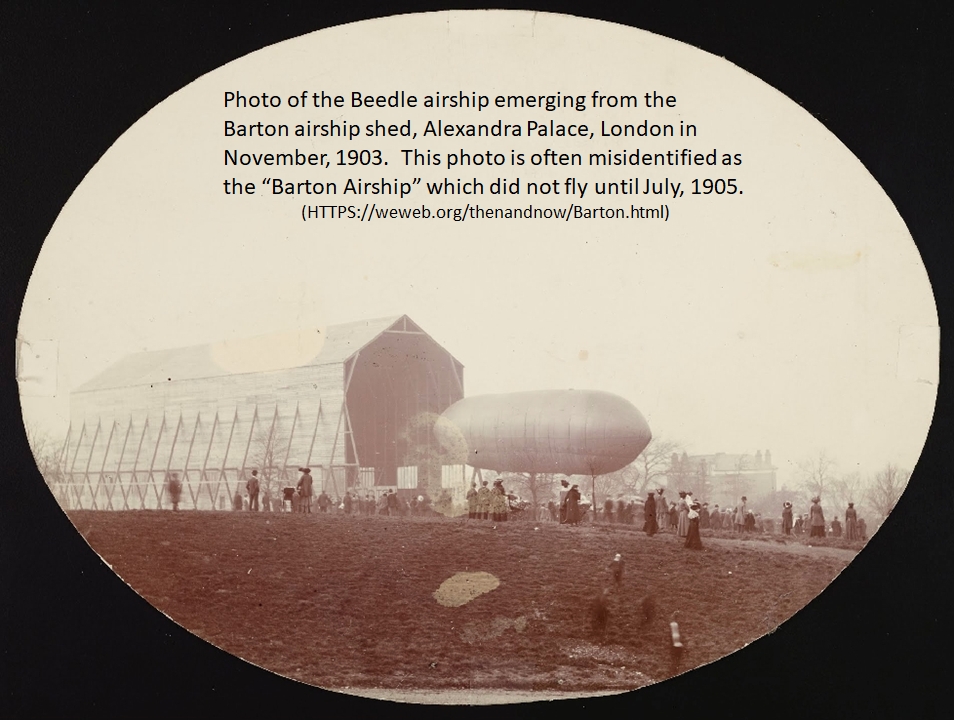

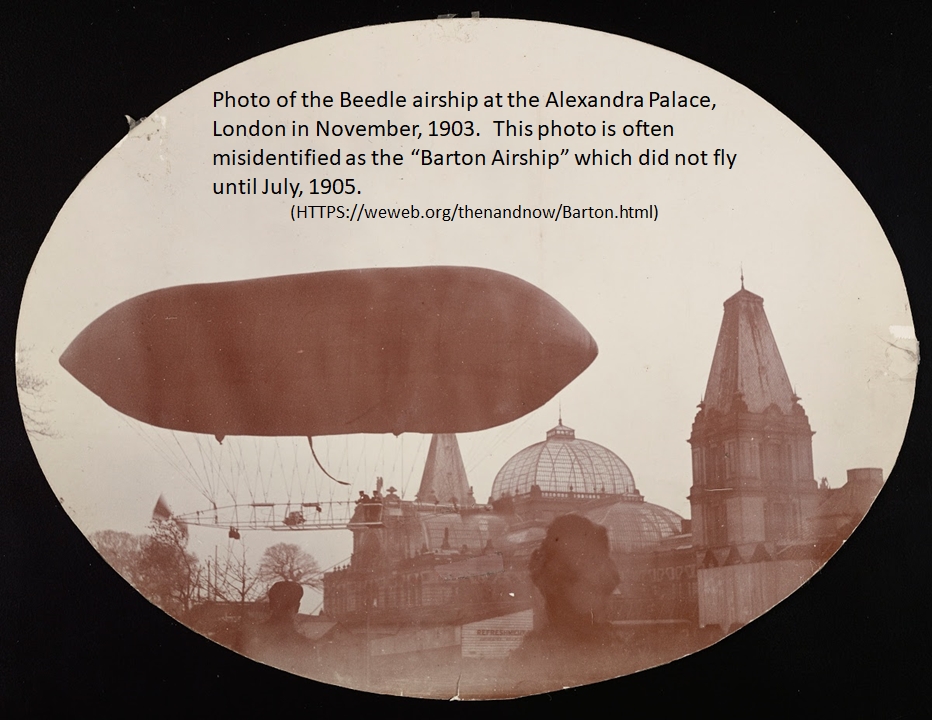

Mistaken Identity

It is not uncommon for airships to be misidentified. Unfortunately, the INTERNET permits the misidentification to be perpetuated far and wide. This is the case for the Barton Airship as well. This next photo, widely found on the INTERNET is often described as the "Barton Airship emerging from the hangar." But it's not the Barton airship! It is the Beedle airship which flew at the Alexandra Palace in November, 1903 and since Barton was not yet using the shed for the full assembly of his airship, Beedle was permitted to use it.

Beedle Airship emerging from Shed. Photo Credit: Public Domain.

And here is a second photo of the Beedle airship also at the Alexandra Palace in November, 1903 which is very often also misidentified as the Barton Airship:

Beedle Airship at the Alexandra Palace, November, 1903. Photo Credit: Public Domain.

(I've marked these two photos with the proper identification as the Beedle Airship to prevent them from being scraped from this page and being propagated further as the Barton Airship.)

Sites of Interest

Alexandra Palace, London, England

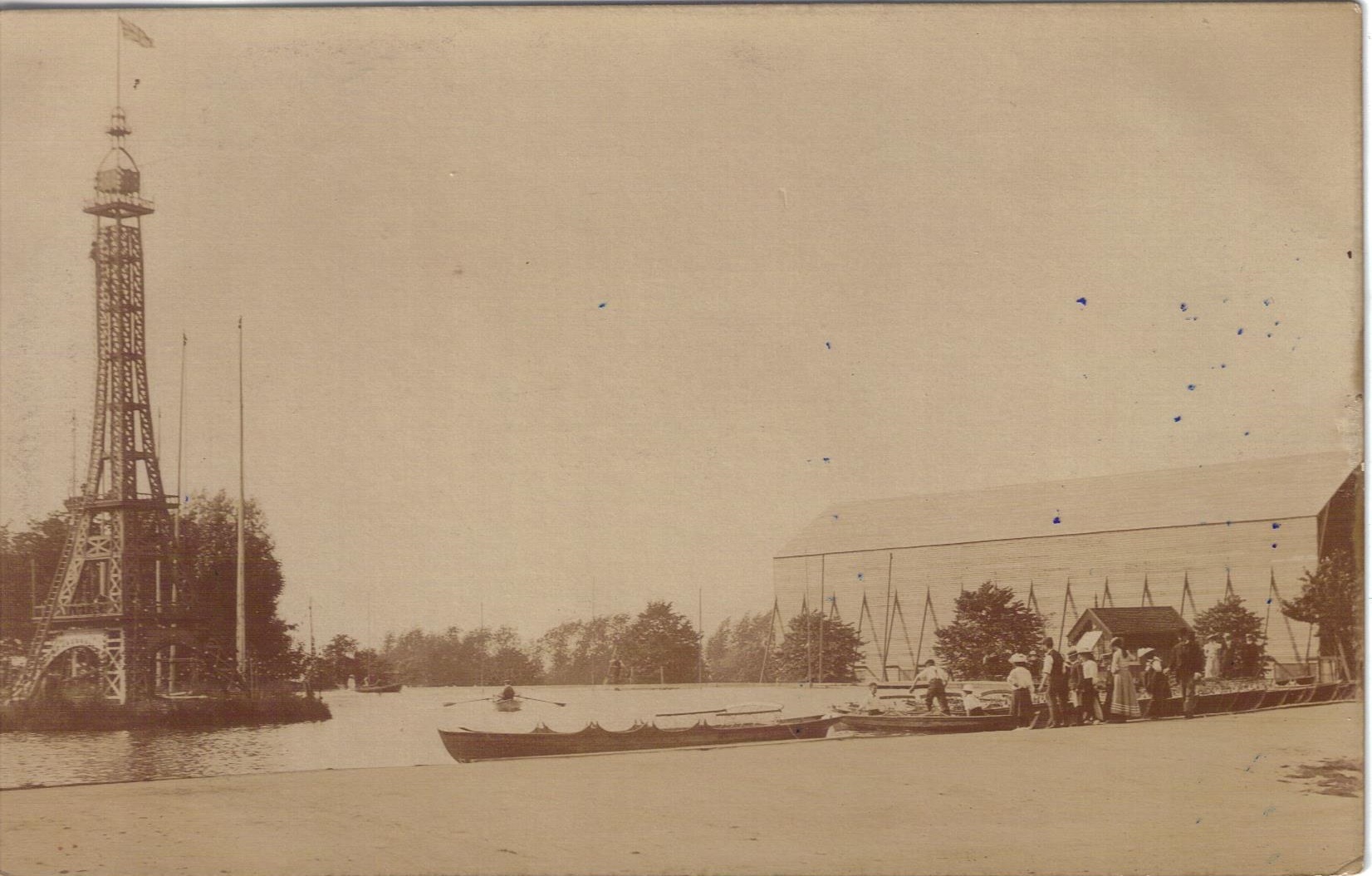

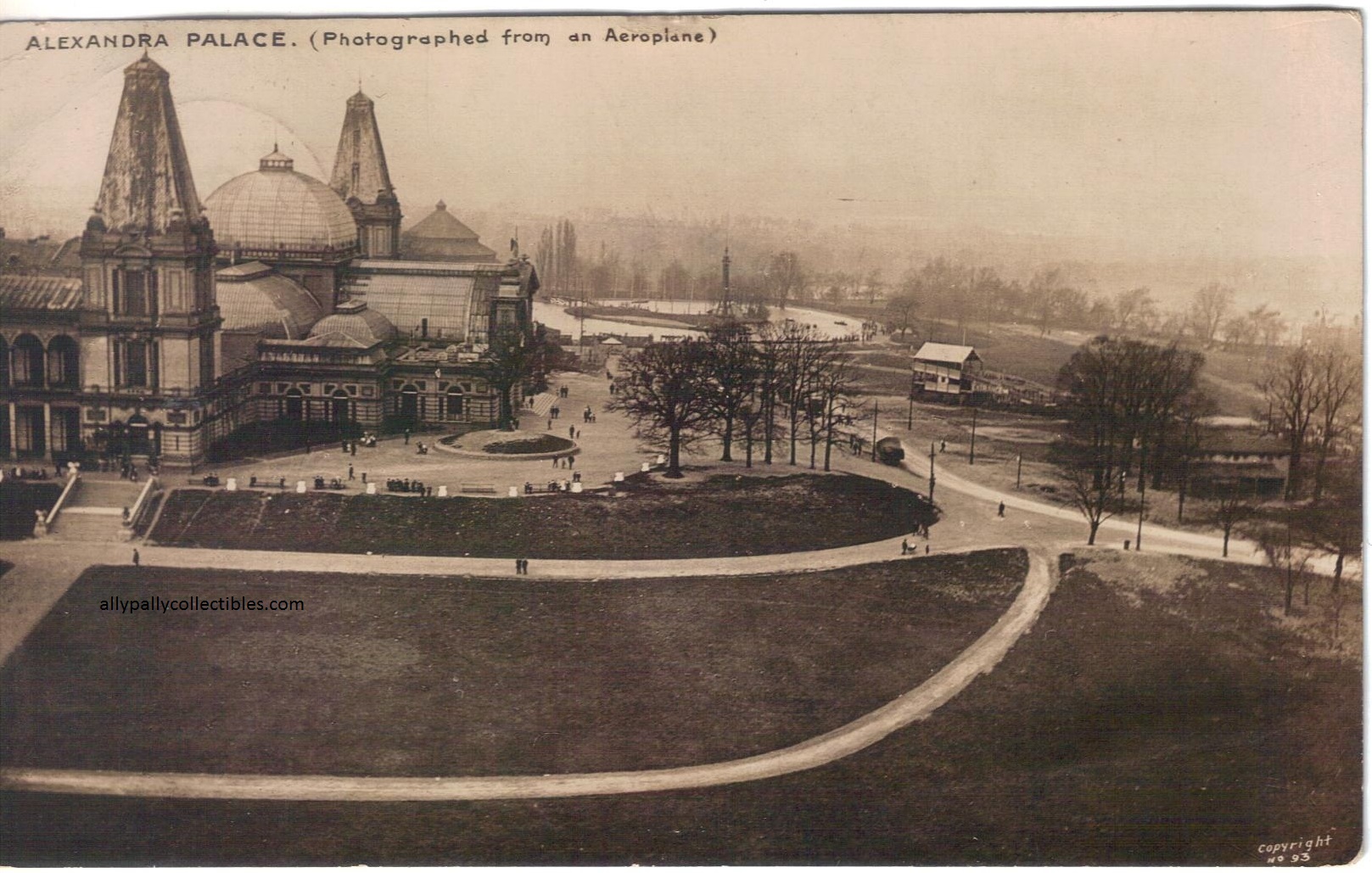

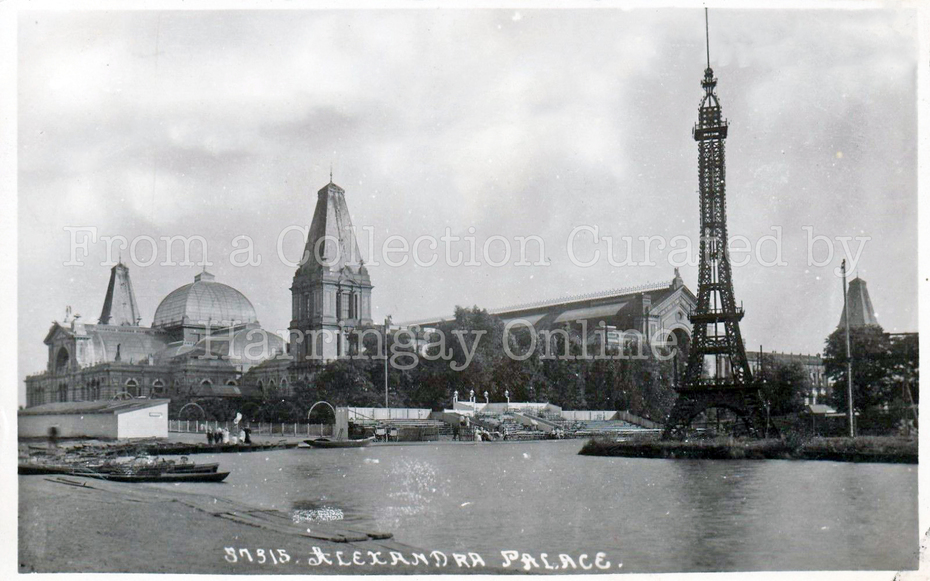

The general site of the Barton airship shed is well-known, as it was near the Alexandra Palace boating lake, but I decided to do a bit of "photo forensics" to see if I could determine the exact (or near exact) location of the shed. Three photos, reproduced below, helped me make this assessment. The first is a nice photo that captures the Shed next to the lake, and the "electric light tower*" that once stood on the island in the lake. The second is a nice shot taken from a kite showing the Alexandra Palace and, in the distance, the lake and the tower. And the third photo is a shot from the lake looking toward the Alexandra Palace with the tower in the foreground. These three photos allowed me to evaluate the orientation of the tower on the lake island, and then determine the position of the Barton Airship shed.

Alexandra Palace lake view showing the electric light tower and the Airship shed.

Photo Credit: Ally Pally 'Museum' (@AllyPallyMuseum) | Twitter.

Alexandra Palace view from a kite with the light tower in the background.

Photo Credit: Ally Pally 'Museum' (@AllyPallyMuseum) | Twitter

Alexandra Palace boating lake looking toward the Palace.

Photo Credit: https://www.harringayonline.com/photo/eiffel-tower-at-ally-pally-1.

Sparing you the details of the "forensic" assessment, I located the shed to have been at (Lat Lon) 51.596625 -000.130566. The red rectangle in the graphic below represents the 55 ft x 182 ft area of the shed. [Click Here to see this location in Google Maps]

Barton Hangar Location, Photo Credit: Google Earth.

*Note: I have no information on this tower. I am calling it the "electric light tower" since upon close examination of the photo, the legs seem to be arrayed with light reflectors. The tower was apparently built in the early 1900s during a time of enormous fascination with the new "electricity" being retrofitted everywhere.

Return to TopI hope you enjoyed discovering this lost history of the Barton-Rawson airship and finding where it was built and enjoyed a very brief existence.

Bill Welker

Colorado Springs, CO, USA

April, 2020