It took me a while to piece together a page on the airships of Alberto Santos-Dumont. No only are there plenty of 100 year old photos to review and potentially identify, but the historical record is voluminous, much of which contains journalistic misinformation and that slowed my research. Santos-Dumont's own 1904 biography is full of errors!

This page is current result of my research about the Santos-Dumont airships and recovering some interesting sites where Santo-Dumont's airships were seen. But I will make note here of the sad end to Alberto Santos-Dumont's life. In 1910, after more than a decade of building dirigibles and heavier-than-air airplanes, Alberto Santos-Dumont "retired" at age 36. He spent the next 26 years of his life apparently suffering from multiple sclerosis and watching his inventions be morphed into a tool of war.

Alberto Santos-Dumont, sadly, ended his own life on July 23, 1932 by hanging himself at the age of 59. May he rest in peace. He is buried in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil.

Navigate Santos-Dumont Airships:

S-D No. 1 , S-D No. 2 , S-D No. 3 , S-D No. 4 , S-D No. 5 , S-D No. 6 , S-D No. 7 , S-D No. 8 , S-D No. 9 , S-D No. 10 , S-D No. 11-13 , S-D No. 14 , S-D No. 15 , S-D No. 16

Jump to Sites of Interest:

No. 9 "Guide-roping" , Château de Bagatelle , S-D Apartment , No. 5 Crash Site , No. 6 Accident , St. Cloud , Aqueduct , "The Cascade" restaurant , No. 6 at St Cloud , Monaco , Neuilly-St James , Santos-Dumont Statue , Bois de Boulogne

Identifying Santos-Dumont Airships

Santos-Dumont built no fewer than 20 aircraft, 15 of which were airships. (Four were heavier-than-air aircraft and 1 was a flying boat!) He did not begin to transition from airships to heavier-than-air until sometime in 1905, only about 4 years before he "retired" after an accident in one of his heavier-than-air machines, but he had spent almost a decade experimenting in lighter-than-air, so there are many Santos-Dumont airships to identify! In the section which follows, I will try to illustrate each one.

Before I begin I must point out two things. First is that many photos of the era, especially post cards, have misidentified Santos-Dumont airships. Especially prevalent is the "No. 5" being mistaken for the "No. 6". Santos-Dumont himself observed this problem. He said in his 1904 book, "My Airships", on page 133: "This was my 'No. 4,' finished 1st August 1900, and by far the most familiar to the world at large of all my air-ships. This is due to the fact that when I won the Deutsch prize, nearly eighteen months later and in quite a different construction, the newspapers of the world came out with old cuts of this 'No. 4,' which they had kept on file." So Santos-Dumont was well aware of the misidentification of his airships by the popular press.

But Santos-Dumont's book did not provide any relief! In fact, it further muddied the waters for the book itself has several illustrations mislabeled. For example, on page 195 the illustration is identified as the "No. 6", while it is in fact the "No. 5" (the airship pictured has no radiator and the location of the pilot's basket is in the 4th "cell" of the keel, not the 3rd). As a second example, on page 215, the illustration is identified as the No. 9, while it is clearly the No. 6! As a 3rd example, on page 267 the No. 14 is identified as the "No. 5."! There are other mislabeled illustrations in the book as well, but I've made my point. These photo identification issues led to many hours of painstaking work to finally determine the visual features of each Santos-Dumont airship and to sort them out.

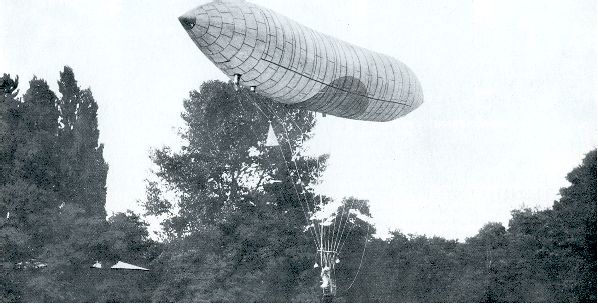

Santos-Dumont No. 1

Built in 1898, the No. 1 flew on the 18th of September of that year. Believe it or not, looking at the figure below, the No. 1 had a gasoline engine and a pusher propeller! It survived only two flights. Following instructions from the "experts" present at the inaugural flight, those "professionals" who had experience in launching spherical balloons, Santos-Dumont launched at the upwind edge of the open space, and as he expected, his propeller-driven craft was quickly driven into the trees before it had time to ascend above them. So the first flight ended in somewhat of a failure except that it served to prove to Santos-Dumont that he was right that his airship would be able to move against the wind.

Two days later, after repairs to the airship, Santos-Dumont tried again, this time launching against the wind, and ascending to around 1300 feet altitude. After proving to himself that he could navigate, he began a descent. Unfortunately, upon descending, the declining hydrogen pressure in the envelope caused the envelope to begin to fold. His air pump, designed to fill a ballonet to compensate for loss of hydrogen pressure, did not have enough power to provided the needed compensation and the elongated gas-bag folded as the enclosed hydrogen gas changed volume, as the outside air temperature varied.

Thus the 2nd flight resulted in a crash significant enough that the No. 1 never flew again. Santos-Dumont was unhurt as he skillfully directed some ground observers to grab a rope and pull the No. 1 into the wind to slow its descent. That worked. Unfortunately, the No. 1 never flew again.

(Note: The 1917 D'Orcy's Airship Manual indicates, on page 91, that the Santos-Dumont No. 1 (and No. 2) did not have a ballonet. Clearly D'Orcy's is incorrect for there would be no need for an air pump to compensate for hydrogen pressure loss if the envelope did not contain a ballonet for air.)

The "Santos-Dumont No. 1"

Photo credit (above): Public domain

Specifications:

- Length: 82.5 ft (25 m)

- Max Diameter: 11.5 ft (3.5m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 7.0

- Operating dates: September 1898

- Visual: Elongated tube with pointed ends, gondola suspended from cables. No keel as found in later Santos-Dumont airships. There is a small rudder visible hanging in the rigging about 1/3 the way down toward the basket. Any photo of a Santos-Dumont in this configuration, i.e., the suspended basket and no keel must be either the No. 1 or the No. 2. See the "visual" for the No. 2, below, for distinguishing features.

Santos-Dumont No. 2

Santos-Dumont made changes to his design from the No. 1 specifically to compensate for the loss of rigidity of the gas envelope during changes in internal pressure of the hydrogen-filled volume. Unfortunately, his changes were not enough to overcome the weather conditions he encountered on the first flight of the No. 2 on May 11, 1899.

That day, the weather was fine when he began preparations for laying out and filling the airship with hydrogen. But in the afternoon, rains came, wetting the envelope, suspension lines, and basket. Trying to avoid loss of the hydrogen, which he has paid for, he opted to ascend. Unfortunately, upon ascending, the changing air temperature caused a loss of hydrogen pressure that none of his countermeasures could compensate for.

As the craft descended, unable to maintain its shape, a gust of wind dashed the No. 2 into some trees. The No. 2 was destroyed.

The "Santos-Dumont No. 2", seen here in its only flight as the hydrogen envelope begins to lose its shape due to the hydrogen gas being cooled by a cool and humid atmosphere.

Photo credit (above): Public domain

Specifications:

- Length: 82.5 ft (25 m)

- Max Diameter: 12.5 ft (3.8m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 6.6

- Operating dates: 11 May 1899

- Visual: Elongated tube with pointed ends, gondola suspended from cables. No keel as found in later Santos-Dumont airships, all very similar to the No. 1. The No. 2 has a larger rudder than the No. 1 visible now attached at the stern of the envelope. Otherwise the ship is indistinguishable from the No. 1 even though the envelope is slightly larger in diameter.

Santos-Dumont No. 3

With the short life of the No. 2, Santos-Dumont quickly set out to correct the problem with the loss of rigidity of the hydrogen envelope. The design of the No. 3 included a shorter length but a much larger diameter envelope as well as elimination of a ballonet with which he had had so much trouble. In place of the ballonet, he affixed a 33 foot long (10 m) bamboo pole between the suspension cords and the aeronaut's basket.

The design of the No. 3 enabled so much lift that Santos-Dumont opted to use "illuminating gas" (coal gas) instead of hydrogen despite the fact that cola gas has a "lifting power" of only about 1/2 that of hydrogen.

Santos-Dumont flew the No. 3 with relative ease, quickly learning its capabilities. So confident he was in the No. 3, he made repeated circles of the Eiffel Tower. Upon landing, he chose a spot very near where his No. 1 was forced down a year earlier.

The "Santos-Dumont No. 3"

Photo credit (above): http://www.thosemagnificentmen.co.uk/blimps/SD2345.html, Public domain.

Specifications:

- Length: 66 ft (20 m)

- Max Diameter: 25 ft (7.5m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 2.6

- Operating dates: November 1899 to some undetermined date in early to mid 1900

- Visual: "Stubby" tube (only about twice as long as it is wide) with pointed ends, gondola suspended from cables. Bamboo "keel". There is a larger rudder than the No. 1 visible again at the stern of the envelope between the envelope and the bamboo keel. These dramatic design differences make it quite easy to identify photos of the No. 3.

The success of the No. 3 led Santos-Dumont to desire his own facility for building and housing his airships. This was most desirable, in part, because now that he could launch and land where he chose, and because his airships lost so little costly hydrogen gas during a flight, it seemed wise to have a hanger in which the fully-inflated airship could be stored between flights. So Santos-Dumont worked with the newly formed Paris "Aéro Club" to secure a location within the Aéro Club grounds at the Côteaux de Longchamps at St Cloud, (Hills of Longchamps at St. Cloud), for his own hangar.

He secured construction immediately, and while the hangar was being built he continued to fly the No. 3. On some unknown date, the rudder of the No. 3 came loose and thought he was able to successfully land the craft, it was not repaired. Since he now had his own 100 foot long hangar, his "aerodrome", and his own hydrogen generating plant he decided the No. 3 had served its purpose and began planning the No. 4.

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 4

Photo credit (above): Public Domain

Samuel Langley observes a flight of the Santos-Dumont No. 4 in September 1900

Specifications:

- Original Length: 95.7 ft (29m) (Later lengthened to 109 ft (33 m))

- Max Diameter: 17 ft (5.1m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 7.6 (later 6.5)

- Operating dates: August 1900 to ~late 1900 (The No. 4 was dismantled and its envelope used in the No. 5.)

- Visual: Very pointed, elongated envelope with a keel of a single bamboo beam on which the pilot sat on a bicycle seat. No basket or gondola. Single tractor-propeller, i.e. propeller at the stem. In the surviving photos, few reveal a rudder but the vehicle did have a rudder mounted at the aft-end of the envelope.

Santos-Dumont writes that he flew the No. 4 "almost daily" from August through September 1900 from his hangar at St Cloud.

The No. 4 was "heavy" and permitted only 110 pounds of ballast. Trials of the No. 4 led Santos-Dumont to replace the motor with a more powerful 4-cylinder engine, and, as a result of the added weight of the new engine, he had to lengthen the envelope to increase the volume of hydrogen. The "new" No. 4 was 109 feet long (33 m), now more than 13 feet longer. Unfortunately, the longer No. 4 caused him to also enlarge his hangar at St. Cloud to 113 feet! (And note this: The No. 4 and the hangar were both modified in 15 days! Try that in today's construction environment!)

Santos-Dumont wanted to display the No. 4 at the World's Fair in Paris which was held from April 14, to November 12, 1900. Upon completion of his work to enlarge the No. 4 he was met with the most foul autumn rains and while waiting for the weather to clear, he collapsed the No. 4 and experimented with improving the engine performance and making changes in the propeller. Unfortunately, Santos-Dumont fell ill to pneumonia and was forced to flee Paris for Nice to recuperate.

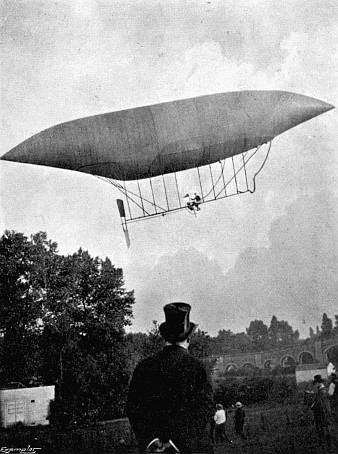

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 5

At Nice, he worked on a new form of a keel made of a light-weight triangular frame of pine. There, he invented the well-known triangular keel we see in photos of many airships of the early 1900's. His first use of the new keel design was in the No. 5.

The "Santos-Dumont No. 5"

Photo credit (above): Public Domain

Specifications:

- Length: 109 ft (33 m) (Reused the envelope of the No. 4.)

- Max Diameter: 17 ft (5.1 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 6.5

- Operating dates: July 11, 1901 to August 8, 1901

- Visual: Reused the No. 4's enlarged, elongated envelope with very pointed ends. A nearly equilateral triangular rudder suspended between the envelope and the keel. A full, triangular-framed keel, the first time used. The engine mounted on the keep is an air cooled engine, so there is no radiator. There is nothing mounted on the keel above the top rail, that is, the fuel tank is "in-line" with the top rail of the keel. The pilot's basket is located in the 4th "cell" back from the front of the keel.

Santos-Dumont desired the No. 5 be the airship with which he would win the Deutsch Prize but it was not to be. On July 11th, 1901 he attempted the course but lost control of his rudder and, losing time in the repairs, did not complete the course in the required 30 minutes. He tired again the next day, but experienced difficult winds and had engine trouble resulting in a crash landing in some trees and sustaining some damage. Finally, he tried again on August 8th. After rounding the Eiffel Tower, he experienced serious loss of hydrogen due to a malfunctioning valve and the No. 5 was lost against the high-rises of the Trocadero Hotels in Paris. Nevertheless, Santos-Dumont already had the design of his No. 6 in mind...

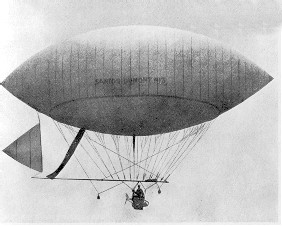

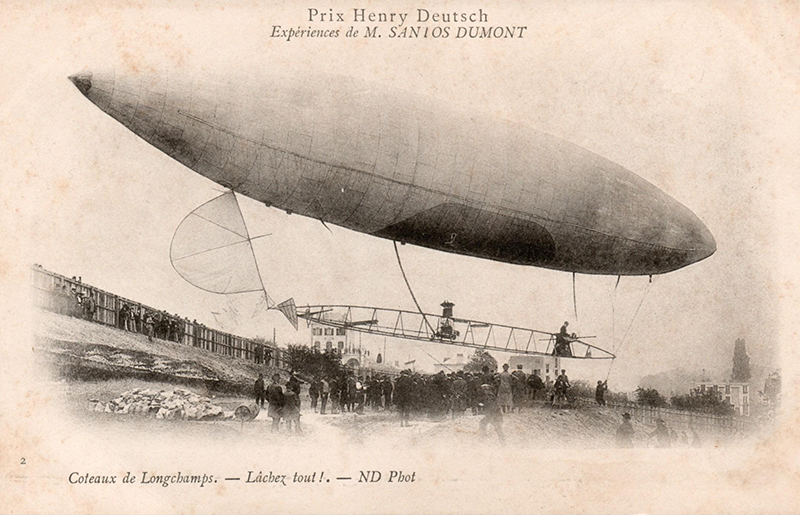

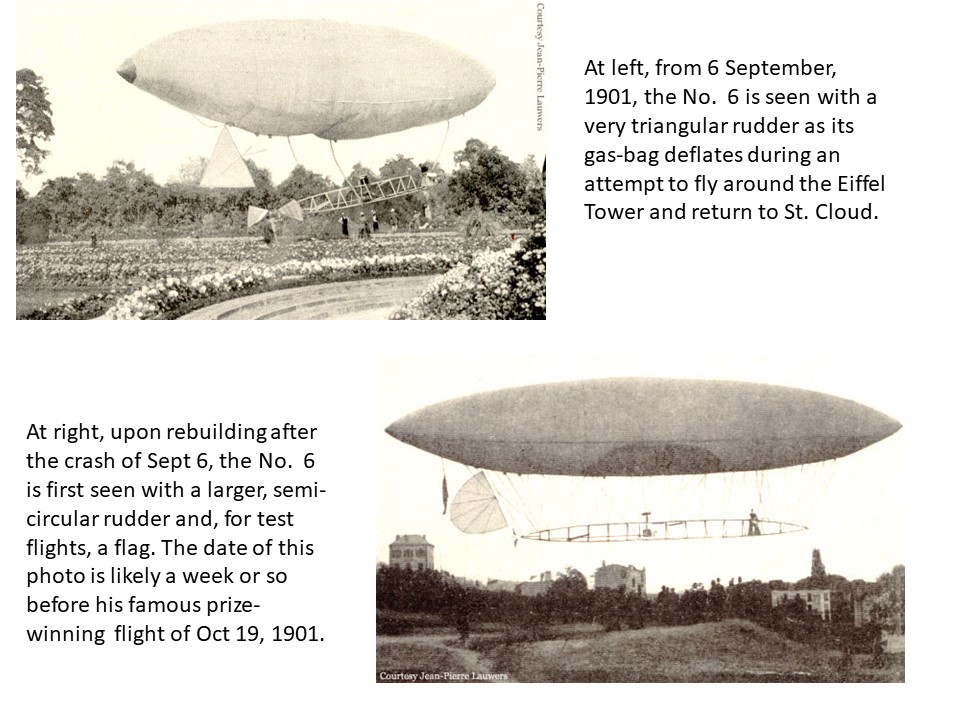

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 6

Santos-Dumont began his No. 6 immediately after the No. 5 crashed. The No. 6 was completed just 22 days after the 8 Aug 1901 crash of the No. 5. Having suffered mechanical failure in his other airships, he paid special attention to the gas valves for both the hydrogen-filled main envelope and the air-filled ballonet. During the course of testing the No. 6 between early September and the 19th of October he had at least two accidents.Santos-Dumont did not record in his book the situation or cause of the accident of 6 September, 1901, but he says it crashed into trees on 15 September, 1901 due to making too sudden a turn. Nevertheless, the No. 6 was ready on 19 October, 1901 for his attempt at the Deutsch Prize, which he won.

The "Santos-Dumont No. 6"

Photo credit (above): Public Domain

Specifications:

- Length: 109 ft (33 m)

- Max Diameter: 20 ft (6 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 5.5

- Operating dates: Late August/early September 1901 to February 14, 1902

- Visual: The No 6. is not as "pointed" as the No. 5. The No 6. has end caps on both the stem and stern of the envelope while the No 5. had no end caps. The pilot's basket sits in the 3rd "cell" of the keel while in the No. 5, the pilot's basket was positioned in the 4th cell. There is a visible radiator, midway along the keel, mounted above the keel. The No. 5 had no radiator. In photos of the No. 6 prior to 19 Oct, 1901, the No. 6 had a triangular rudder similar to the No. 5 making photo identification difficult. But by 19 October, the rudder was a semi-circular version. Also, the "dark oval" of the ballonet at the bottom of the envelope of the No. 6 was centered on the envelope, only slightly forward of the center of the keel while in the No.5, the oval of the ballonet was noticeably aft of the center of the keel.

Here is a comparison of the configurations of the No. 6 between September and October, 1901:

Photo credit (above): Both photos: Jean-Pierre Lauwers collection

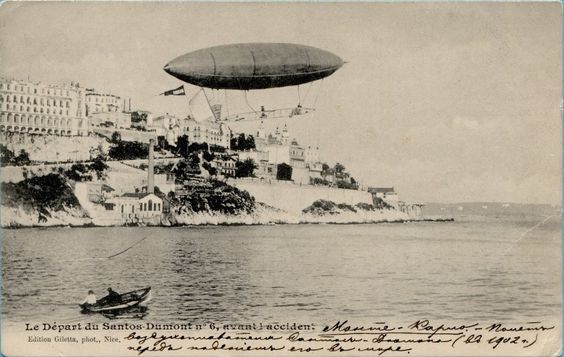

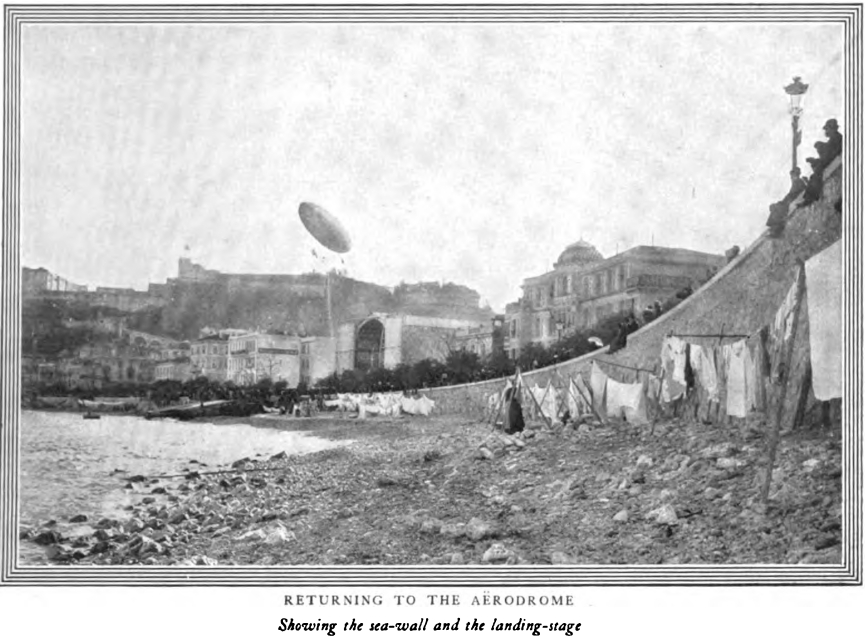

After winning the Deutsch Prize, Santos-Dumont accepted an invitation from the Prince of Monaco to spend some time in Monaco where he could fly unfettered over the Mediterranean. To sweeten the deal, the Prince would build Santos-Dumont an airship shed on the beach of La Condamine. Santos-Dumont accepted the offer and transported himself and his No. 6 to Monaco in January 1902.

At Monaco, the Prince had constructed Santos-Dumont an enormous shed for his airship, complete with doors which Santos-Dumont loved so much for his hangars. Though flying the No. 6 to and from the hangar at La Condamine was fraught with perils, Santos-Dumont accomplished what might very well be an unprecedented and unreplicated feat.

On the morning of January 29th, 1902, Santos-Dumont returned to the hangar after having completed his first voyage out into the Mediterranean. Upon returning, he found the conditions ideal, no wind. After crossing the sea wall between the ocean and his hangar, he cut the engine of the No. 6, and literally "flew" the airship into the hangar without aid from the helpers below! This may well be the only recorded time in history when an airship pilot flew his airship directly into the hangar. Santos-Dumont admits in his book this was not a particularly wise thing to do, and conceded he should not be so bold as to ever try it again!

Santos-Dumont continued to test his No. 6 at Monaco into February, 1902. Unfortunately, on February 14th, he met with disaster. The No. 6 had departed the hangar improperly inflated and configured for flight - a condition Santos-Dumont attributes to the poor conditions near his hangar at Monaco which did not permit his ascending into the higher atmosphere before he flew out into the Mediterranean where the changing temperatures in the sun, above the water produced dramatic pressure differences in the envelope. The airship began to point up, stem first, higher and higher beyond design limits. Some of the rigging wires became entangled in the propeller and Santos-Dumont was forced to shut of the engine. At that point his only choice was to release hydrogen for a controlled decent to the ocean surface, where it was damaged but recovered.

Photo credit (above): Jean-Pierre Lauwers collection

The No. 6 descending into the Mediterranean on its last flight, February 14th, 1902.

A bit of mystery surrounds the ultimate fate of the No. 6. Santos-Dumont says in his book, page 256, that the flight in Monaco, 14 February, 1902 was its last voyage - the implication being that the No. 6 never flew again. And on page 258, he states the "Balloon, keel, and motor were successfully fished up the next day and shipped off to Paris for repairs." But on page 318 he says that the envelope of the No. 6 was retrieved from the bay of Monaco and sent to London for inflation and display at an exhibition at the Crystal Palace. No mention is made about the No. 6 being sold to anyone. Paul Hoffman in "Wings of Madness", page 196, when Santos-Dumont had returned to Europe from an April, 1902 visit to America says: "He [Santos-Dumont] revealed that he had sold the No. 6, which was being repaired in London, to the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company".

Paul Hoffman records that Santos-Dumont travelled to London in late May, 1902 to inspect the progress of the restoration of the No. 6, the envelope of the airship was found slashed when workers were preparing to reassemble the craft in a new shed built next to the Crystal Palace. A new envelope was made for the No. 6 and the entire airship was shipped to New York in July.

Though Santos-Dumont returned to New York that summer and inspected the resurrected No. 6, several accidents to the airship occurred and that, combined with Santos-Dumont's disgust with the progress of his arrangements to fly his airship in America, Santos-Dumont quietly returned to Europe refusing any further dealings with his American contacts. But the mystery deepens because there are many articles and newspaper stories in the fall of 1902 which describe the No. 6 being flown in New York by Mr. Edward C. Boyce (sometimes spelled "Boice") and that the airship had been at Brighton Beach "all summer"! An entry in the 1902 "Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events of the Year", page 5, after discussing the accident with the No. 6 while in Monaco, says: "This balloon, No. 6, with some slight alterations, was brought to the United States in July, 1902, and was used at Brighton Beach by Mr. Edward C Boice in his ascent on Sept. 30, 1902."

A story in the October 1, 1902 "The Evening Times" (Washington DC), says curiously: "NEW YORK Oct 1. America had its first race of airships yesterday. The contest was between Santos-Dumont No. 6, the big airship which the Brazilian would not go up in and which has been at Brighton Beach all summer". The article goes on: "The Santos-Dumont was operated by Edward C Boyce...a member of the Aero Club and his flight was in fulfillment of his declaration that the Santos-Dumont No. 6 should fly if he had to take her up himself." Evidently Mr. Boyce was the new owner of the No. 6. (I should point out that while most sources I located describe the New York airship race as having been on September 30th, some sources state that the race was on September 15th.)

Following that race in September, 1902 I have as yet not found evidence of exactly what ultimately became of the Santos-Dumont No. 6.

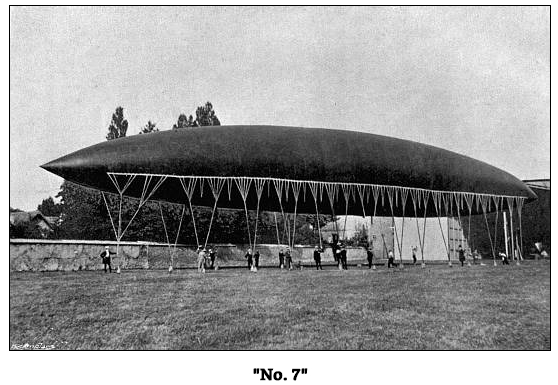

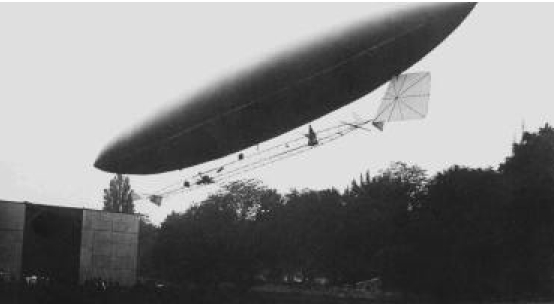

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 7

The No. 7 has a bit of a sordid history. Few details are found on when the airship was designed and built. Few pictures of the No. 7 are found. Most surviving photos show only the No. 7's inflated envelope. The exact date the No. 7 was shipped to St. Louis, USA for the 1904 exposition is unclear. The record of just what happened to the No. 7 after it arrived in St. Louis is not clear. All we actually know is that sometime after arrival in the US, and preparation for the exposition, the No. 7's envelope was found in its shipping crate slashed in four locations. It had been inspected upon arrival and found in good shape so the envelope was destroyed sometime after arrival in St. Louis. The No. 7 was destroyed for reasons which remain unclear to this day, though sabotage is assumed.

The "Santos-Dumont No. 7"

Photo credit (above): Public Domain

This popular, undated photo (probably late March, 1904) shows the inflated envelope of the No.7 held down by sandbags in a static test. No keel, engine, propellers, rudder, or pilot's basket are seen.

Photo credit (above): http://www.hydroretro.net/etudegh/machines_volantes_santos-dumont.pdf

This is the only photo I was able to find of the No. 7 in flight test. The shot shows the No. 7 at Santos-Dumont's hanger at Neuilly-St. James and is dated to between 16 May, 1904 and the 1st part of June. The No. 7 was shipped to St. Louis on the 9th of June.

Specifications:

- Length: 160 ft (~50 m)

- Max Diameter: 26 ft (~8 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 6.25 (but tapers sharply to points at each end, rather than rounded like most large envelopes (such as the No. 10)

- Operating dates: (Design began in 1902, construction in May, 1903). Operational tests from 16 May, 1904 to the end of May. No further testing is known. The No. 7 was shipped in early June, 1904 to St. Louis, USA, and the envelope was destroyed, reportedly by sabotage, shortly after it arrived. The airship had been shipped to St. Louis for display and racing at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904.

- Visual: Few pictures exist of the flight-ready No. 7. At 160 feet long, its keel measured approximately 90 feet long. The pilot's basket sat in the aft, far from the engine instead of forward where it usually was positioned. The pilot was about 42 feet from the engine! The No. 7 had two propellers, one at the stem and one at the stern. The rudder was a large rectangle attached at an oblique angle at the hinge.

Santos-Dumont No. 8

Some sources, including Paul Hoffman in "Wings of Madness", say there was no "No. 8" since it is rumored Santos-Dumont was superstitious about the number. D'Ocy's (1917) lists lists a Santos-Dumont No. 8 making only one ascent and being dismantled after proving unsatisfactory. Santos-Dumont makes no mention of a No. 8 in his 1904 book. A French source "Les machines volantes de Santos-Dumont" by Gérard Hartmann states (via a rough machine translation to English): "From the beginning of the year 1902, to replace the No. 6, No. 8 is equipped with 4-cyl 16 or 20 hp more recent but the same mass as Buchet 12 hp. The airship was purchased by the future president of the Aero Club of America (formally established in 1905), Mr Boyce. Delivered in New York during the summer of 1902, the machine was destroyed during its first flight on a beach in northern New York." [Note: If the dates in the French article are correct, the No. 8, may very well have been the restored No. 6 as the No. 6 was shipped to the US that summer - see text, above.]

The June 18th, 1904 Scientific American confirms that Santos-Dumont built a "No. 8" and sold it to a "Mr. Boyce" of New York. The article says (while discussing Boyce's purchase that year of the No. 9): "Mr. Boyce had previously purchased the No. 8, but had an accident with it during his first ascensions." A statement by Luiz Pagano in a May, 2011 posting on Blemya.com about the inventions of Santos-Dumont says the No. 8 was an exact duplicate of the No. 6, also confirming that it was destroyed in New York on its first flight.

As briefly mentioned above, print evidence also seems to indicate that Edward Boyce also purchased the Santos-Dumont No. 9, though Santos-Dumont mentions no such fate of the No. 9 in his book. A 2012 post on the "aerodrome.com" (http://www.theaerodrome.com/forum/showthread.php?t=56141) website says "In 1904 S-D brought the No. 9, along with the No. 7 'Racer' to the US. The No. 7 continued onto St. Louis while the No. 9 stayed in New York where it was exhibited at Dreamland amusement park at Coney Island. Edward C. Boyce, the amusement park tycoon and part owner of Dreamland, soon after bought the Baladeuce as he had the Santos-Dumont No. 6 a couple of years earlier." Page 24 of the "Report of the National Museum, 1907" states: "The Santos-Dumont airship No. 9, was presented to the Museum by Mr. Edward C. Boyce, of New York."

The "Santos-Dumont No. 8"

I have found no photos of any airship I could identify as the Santos-Dumont No. 8, built by Santos-Dumont or owned by Edward Boyce of New York. (The article cited above on Blemya.com has a drawing of the No. 8 which assumes its profile similar to the No. 6.)

At this point in my research it seems that there may have been a No. 8 which had been purchased by Mr. Boyce of New York. But it also seems possible that the "No. 8" mentioned in reports of the day was, in fact, the restored No. 6. Either way, the fate of the ship remains unknown.)

Specifications: Unknown

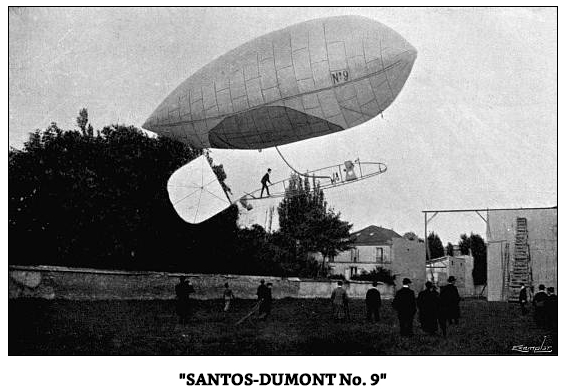

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 9

The No. 9 may very well be unique in airship history. Though many small airships have been built, the No. 9 of Santos-Dumont may be the only airship in history to have been built, in his own words: "for my pleasure and convenience only." He literally built the No. 9 to kill time waiting for a worthy competitor to bring forth an airship to compete against him!

The No. 9 appeared in two configurations. In the 1st version, the envelope held 7770 cubit feet of hydrogen permitting only 66 pounds of ballast. After a few weeks of testing he enlarged the envelope of the No. 9 by nearly 20%, permitting 132 pound of ballast. This became the 2nd version seen in most photos of the No. 9.

The "Santos-Dumont No. 9"

Photo credit (above): Public Domain

The No. 9 at Neuilly-St. James. The No. 9 proved to be a remarkable airship of enormous maneuverability. Santos-Dumont could fly it "at-will" even landing on busy streets in front of Paris pubs! The No. 9 is also known as "La Balladeusse".

Photo credit (above): Public Domain

This photo is one of several well-known photos of the No. 9 landing in Paris on one of Santos-Dumont's many pleasure trips in his "runabout". It is most often assumed to be in front of his apartment building along the Champs-Élysées. It is not! After rather intensive study, I identified the precise location of this photo - see "Sites of Interest" below.

Specifications:

- Length: 50 ft (~15.1 m)

- Max Diameter: 18 ft (~5.5 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 2.75

- Operating dates: 1903

- Visual: Stubby nose, pointed tail, short keel, pilot's basket forward of the engine very close to the stem. Large, semi-circular rudder.

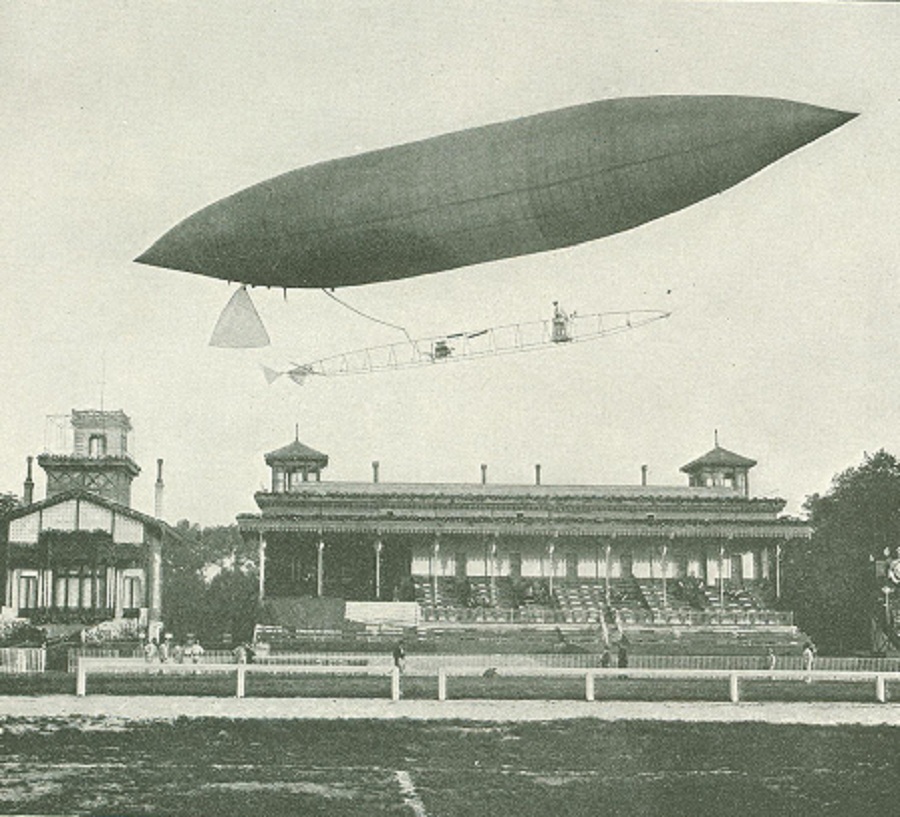

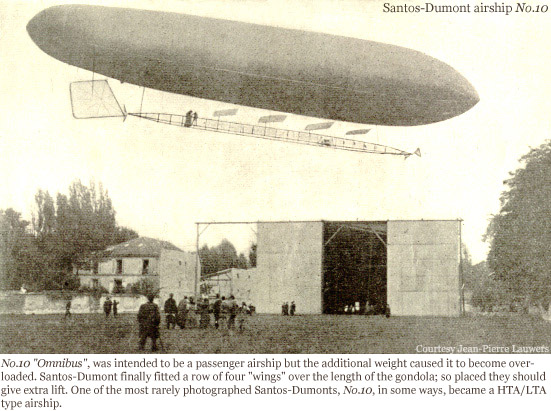

Santos-Dumont No. 10

The No. 10, the "Omnibus", was an ambitious project. It was intended to be a passenger-carrying craft capable of carrying 10-12 people. In addition to the long keel carrying the engine, propeller, rudder and pilot, there was to be a second keel suspended below it in which passengers would ride in 3 baskets - up to four people per basket. Clear in photos of the No. 10, Santos-Dumont had begun to consider airplane flight. Mounted above the keel, between the envelope and the keel were 4 "wings". Presumably, during forward motion, these "wings" would provide some small lift to the craft permitting the airship to ascend even if it was not fully buoyant but was slightly heavier than air.

The "Santos-Dumont No. 10"

Photo credit (above): Jean-Pierre Lauwers collection

Here the No. 10 is seen in one of the rare photos of the craft. It was taken on 19 October, 1903 - two years to the day after Santos-Dumont's successful flight in the No. 6 which won the Deutsch Prise in 1901. It is being tested at Santos-Dumont's grounds at Neuilly-St. James. In the background is Santo-Dumont's large hangar in which he could house more than one airship.

Just as there are few photos of the No. 10, indicative that there were few test flights, there is no evidence that Santos-Dumont ever flew the No. 10 with the passenger keel or with passengers.

Specifications:

- Length: 157.5 ft (~48 m)

- Max Diameter: 27.9 ft (~8.5 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 5.6

- Operating dates: 1903

- Visual: Very long and rounded envelope with a very long keel. Pilot's basket toward the aft, engine forward. Propeller on the keel at both stem and stern. A large trapezoidal rudder. A set of four horizontal stabilizers, "wings", were positioned along and above the keel. Easily distinguished from the No. 6 by the longer keel and envelope with the ends of the envelope more rounded than the No. 6.

Santos-Dumont No. 11

The No. 11 was not an airship, rather it was an experiment in aeroplanes.

Santos-Dumont No. 12

The No. 12 was not an airship, rather it was an experiment in helicopters. Photos exist of the the No. 12 in the shed, but it was never completed.

Santos-Dumont No. 13

The No. 13 was an odd balloon. Intended as a "hybrid" hydrogen-filled balloon with a lower envelope for conventional hot air, the craft was built but never completed. Probably a good thing!

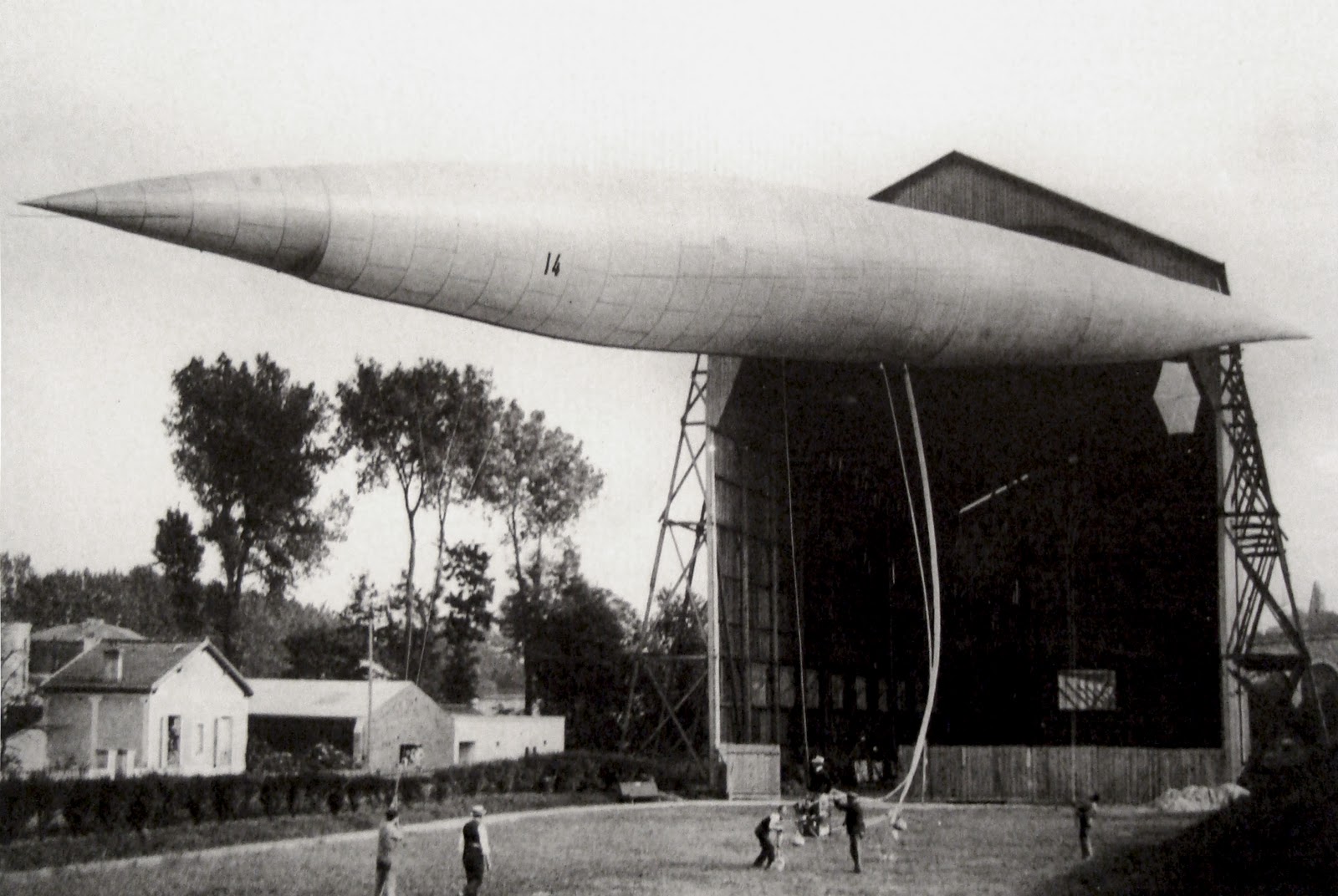

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 14

Not much is found on the No. 14. Even why Santos-Dumont built the No. 14 is not well understood. What is known is that he designed the airship in Paris but spirited the craft to the shores of Trouville beach on the English Channel where he was pleased with its performance.

Some time after testing the No. 14, Santos-Dumont met up with a Mr. Gabriel Voisin, and the two of them began designing an aeroplane. The airship No 14 was redesigned such that the envelope was shortened and widened and photos of the era show the No. 14 was tested again in this new, 2nd configuration. In July 1906, the gondola of the No. 14 was removed and in its place an aeroplane was suspended. The No. 14 airship had become a "tug" of sorts. Using the No. 14, Santos-Dumont tested the air-worthiness of his aeroplane, the 14-bis ("14-encore").

The "Santos-Dumont No. 14"

Photo credit (above): Jean-Pierre Lauwers collection

The No. 14 in its initial configuration, with its very long, narrow envelope, and very small pilots' basket/gondola.

Photo credit (above): Jean-Pierre Lauwers collection

The No. 14 in its 2nd configuration with a noticeably shortened, and larger diameter.

Specifications:

- Length: (Initial configuration) 134.5 ft (~41 m)

- Max Diameter: (Initial configuration) 11.2 ft (~3.4 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 12

- Operating dates: August 1905 to August 1906

- Visual: In its initial configuration, a stunning, long, extremely pointed envelope with a small gondola hung quite a distance from the gas-bag. No long "keel" as Santos-Dumont had been using. Pilot's basket, engine and propeller very much like the No. 1, though the frame surrounding the basket was like a shortened No. 9. In its second configuration, the same gondola, with a shortened and fatter envelope. Both configurations used a hexagonal-shaped rudder.

Santos-Dumont No. 15

The No. 15 was an unsuccessful biplane.

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 16

The No. 16 was a curious hybrid. It was a small airship, combined with a framework hanging below of a sort of aeroplane framework consisting of lifting surfaces (wings), a rudder, an engine and wheels. It did not survive its first test flight though reports vary from "it fell apart on the ground" to "stranded on a tree while landing after her first ascent."

The "Santos-Dumont No. 16"

Photo credit (above): Jean-Pierre Lauwers collection

One of the few photos/post cards of the No. 16. Even if enhanced by an artist, you can see the key features of the No. 16 and its interesting diversion from the established Santos-Dumont designs.

Photo credit (above): Getty Images

Against my better judgement, I am posting this very fine image of the No. 16, shamelessly being sold by Getty Images, when, over 70 years old, the image should be released to the public domain. (Should Getty Images want me to remove this image, all they have to do is let me know and I will do so.)

Specifications:

- Length: 69 ft (~21 m)

- Max Diameter: 9.8 ft (~3 m)

- Envelope ratio (L/D): 7

- Operating dates: June, 1907 - 8 July 1907

- Visual: Widely deviant from all other Santos-Dumont airships. Small, pointed envelope with a short keep supporting an engine and pilot's basket and lifting surfaces clearly for an airplane. A hexagonal rudder.

Sites of Interest

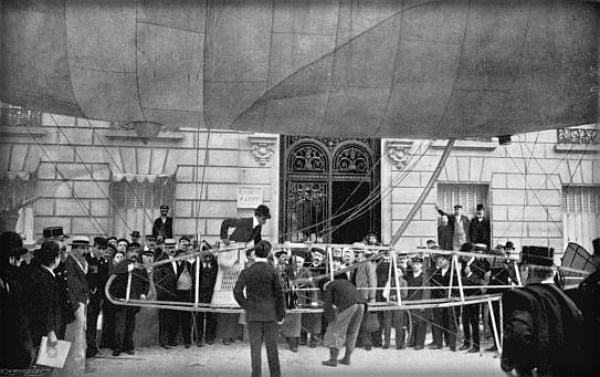

"No. 9 Guide-roping on a Level with the Housetops"

In Santos-Dumont's book "My Airships" he is seen in this photo piloting the No. 9 as the caption reads "No. 9 Guide-roping on a Level with the Housetops". This photo is widely published in many articles about Santos-Dumont. In my research it became clear that most assume the shot was taken on the Champs Elysées at Rue Washington - the location of Santos-Dumont's apartment in Paris. But the actual location, as seen below, is a little over a mile (1.8 km) west of the Santos-Dumont apartment.

Photo credits (above): Public domain

Here is a second shot of the same location with the No. 9 on the ground and a large crowd gathered.

Photo credits (above): Public domain

Here is location today. It's at the intersection of Avenue Bugeaud and Boulevard Flandrin at the Place du Marechal de Lattre de Tassigny, (Lat Lon) 08.871227 002.275801:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth (perspective corrected)

In Santos-Dumont's time, "Avenue Foch" was known as "Avenue du Bois de Boulogne" for Santos Dumont accurately describes the avenue as the beginning of the broad avenue from Porte Dauphine, which leads directly to the Arc de Triomphe. This is unquestionably today Avenue Foch.

And the location on Google Maps:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

Return to topNo. 9 near the Château de Bagatelle

Among the many photos of Santos-Dumont airships, many have identifiable buildings in the background which still survive today. A good example is the Château de Bagatelle, where multiple photos of the No. 9 reveal the Château in the picture. This location was, of course, easy to find!

Photo credits (above): Public domain

Here is a delightful 2nd shot of the No. 9 near the Château

Photo credits (above): Public domain

Here is location today with the map-tack at the approximate location of the No. 9 in the first photo, above. The location is (Lat Lon) 48.872890 002.245590:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

Return to topSantos-Dumont's Apartment on the Champs Elysées

Here is the famous photo of the Santos-Dumont No. 9 in front of his apartment on the Champs Elysées at 114 Rue Washington.

Photo credits (above): Public domain

This location is well known, in fact, France has seen it fit to mark the building for its historical significance:

Photo credits (above): Undetermined

Here is location. It's at the intersection of the Champs Elysées and Rue Washington at (Lat Lon) 48.872086 002.301169:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

Look carefully at the photo above, to the right of the large, arched door and you will see the plaque of the previous photo commemorating the residence of Santos-Dumont.

And the location on Google Maps:

Photo credits: Google maps

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 5 Crash Site

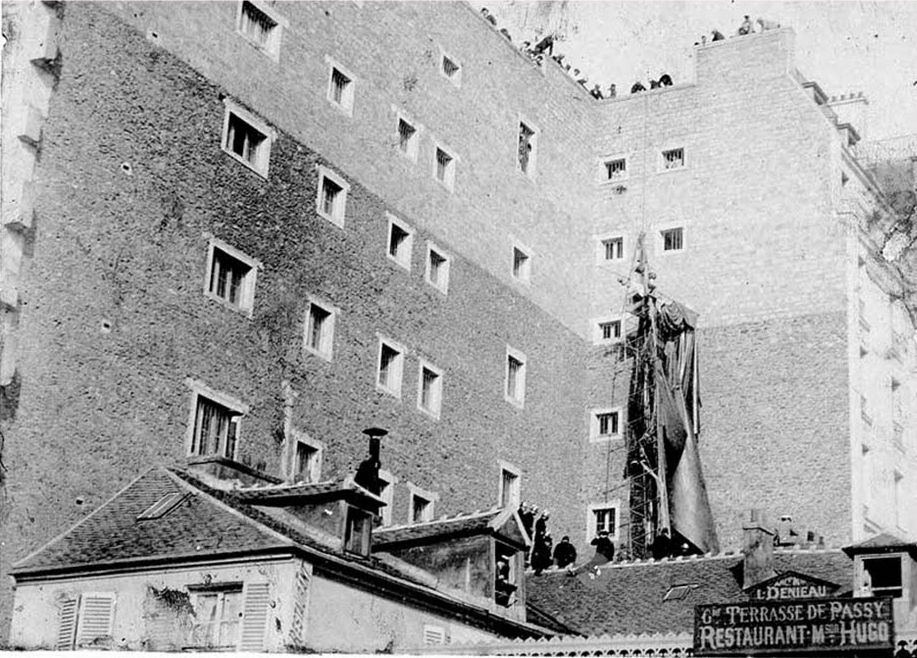

On the 8th of August, 1901, Santos-Dumont had what he described as a "terrible day". On a trip to the Eiffel Tower in his No. 5, he began losing hydrogen. As he was attempting to win the Deutsch Prize, he made a bad decision to press-on. Enough gas was lost that suspension wires became caught in the propeller and he had to cut-off the motor. He had already rounded the Eiffel, but was descending uncontrolled. The winds blew him backward and he crashed into the Trocadero hotel complex. The No. 5 was destroyed but Santos-Dumont survived with only minor injuries and a bruised ego.

Photo credits (above): Public domain

This location is not well known, but by a rather lengthy study of Santos-Dumont's description of the events of the crash, and knowing the association with "Passy" suburb of Paris from the No. 5 crash photo above, led me to locate the crash site. I found an old post card which was oriented in nearly the exact direction which Santos-Dumont described as he rounded the Eiffel Tower, and flew against the wind back toward St. Cloud, passing by or over Passy. A group of buildings at the right side caught my eye:

Photo credits (above): Public domain

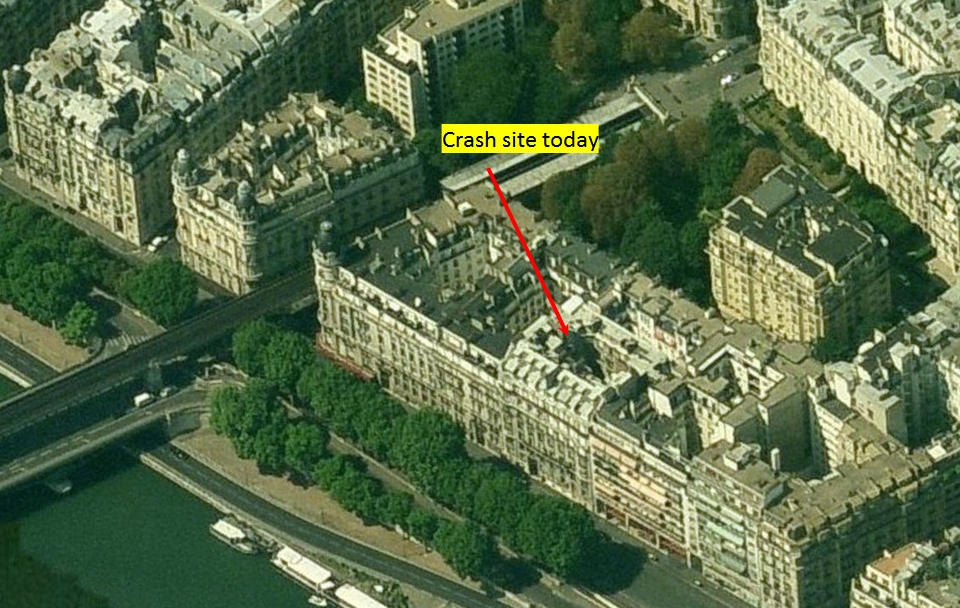

Examining those buildings closely, I found an exact match to the brick walls and windows seen in the No. 5 crash photo! Even the building in the foreground of the crash photo matches the building in the No. 5 crash photo. This is the crash site:

Photo credits (above): Public domain

There is no doubt that this is the crash site. There are many features in the photo above which match the No. 5 crash photo.

An here is the crash site as seen today. It's at (Lat Lon) 48.857503 002.286766:

Photo credits (above): Bing Maps

And the location on Google Maps, along Avenue du Président Kennedy:

Photo credits (above): Google Maps

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 6 Accident at Edmond de Rothchild's Garden

On 6 September, 1901, during a routine morning flight of his new No. 6, the guide rope became entangled in some wires, and the craft was damaged when the keel his a house. He was forced down but made it to the estate of Edmond de Rothschild. Many photos exist of the No. 6 floundering on the property. Here is an example:

Photo credits (above): Jean-Pierre Lauwers collection

Though the Rothschild estate is in ruins today, it is still easily located. We can assume that the small lake still on the property is in the same location as it was in 1901. Thus, we can locate the general spot on which the No. 6 was forced down, alighting on the lake. It's located at (Lat Lon) 48.850344 002.230484:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

And the location on Google Maps:

Photo credits (above): Google Maps

Return to topSaint Cloud, France Aéro-Parc (Aéro-Club Français)

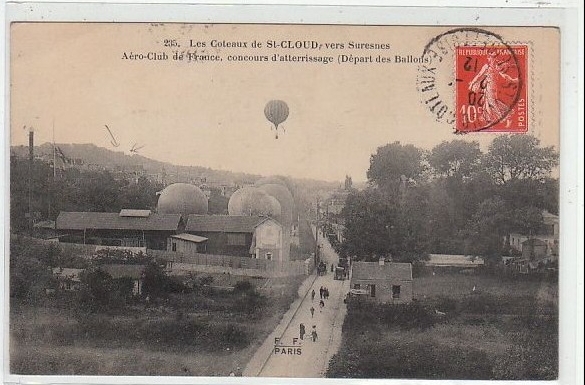

The St. Cloud suburb of Paris, France in the late 1800's became a flying field for the balloons of the era. The Aéro-Club Français secured a large plot of land in St. Cloud and made it their "aerodrome".

One of the early photos I investigated was a long-range shot of several gas-filled spherical balloons clustered on the ground at this "Aéro Club de France". This was the first photo I encountered of the flying field at St. Cloud so I spent time locating it.

Photo credits (above): Public domain

Here is my estimate of the location with a whitespace marked as my estimate of the location of the balloons in the photo. It's at (Lat Lon) 48.858825 002.220291E:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

Here is a perspective view of the same area in an attempt to illustrate why I chose this spot as the location of the balloons. The building on top of the hill in the distance is even still there!:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

And the location on Google Earth:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

This photo, and its location, allowed me to investigate further the area of St Cloud, Paris, France which was so important to the history of Alberto Santos-Dumont.

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 6 Over the Aqueduct at St Cloud

I was now ready to tackle locating exactly where Santos-Dumont flew his No. 6 for his successful flight around the Eiffel Tower in 1901 winning the Deutsch Prize. Seen here is the No. 6 described as taken during the ascent of the airship on its award-winning flight:

Photo credits (above): Public domain

It turns out that the key section of the aqueduct seen in the photo still exists! Had the location not been at St. Cloud, this identification would have been far harder to identify since most of the aqueduct of the era has long since disappeared. I actually spend many months seeking information on the aqueduct system before all the information came together placing the activity at St. Cloud! Here is my estimation of the location of the above photo after careful measurement of the arches in the aqueduct and some photo analysis. My estimated location of the No. 6 in the photo is at (Lat Lon) 48.853356 002.221471:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

And the location on Google Earth:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 9 at "The Cascade" restaurant

I found no photos of any Santos-Dumont landed at "The Cascade" restaurant at the Bois de Boulogne, yet it is known the both the No 6. and the No. 9 were known to land there! Santos-Dumont especially liked landing at The Cascade for lunch apparently because the facility had a large, open grassy expanse directly in front of the restaurant entrance! Here is the location of The Cascade, which is, amazingly, still in operation today more than 100 years later! Its location is (Lat Lon) 48.863191 002.240325:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

Return to topSantos-Dumont flight of the No. 6 at St Cloud

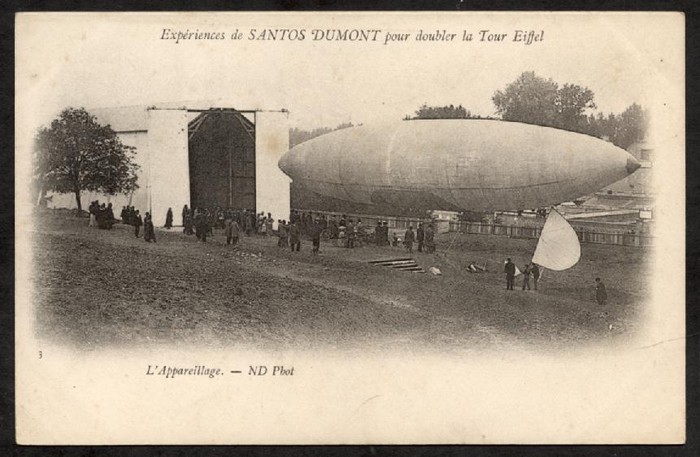

I spent a LOT of time identifying the location of Santos-Dumont's hangar at St. Cloud. It is very confusing because there are quite a few photos of airship operations at St. Cloud, and few researchers, if any, have spent much time trying to sort them out! Santos-Dumont himself said in his book, "My Airships": "The Aéro Club had just acquired some land on the newly-opened Côteaux de Longchamps at St Cloud, and I concluded to build on it a great shed, long and high enough to house my air-ship with its balloon fully inflated, and furnished with all the facilities mentioned." He went on to demand that his hangar would have doors. So it follows that the hangar at St. Cloud belonging to Santos-Dumont would have doors! Here is one of many photos showing the No. 6 at the Santos-Dumont hangar at St. Cloud. Note the doors.

Photo credits (above): Public domain

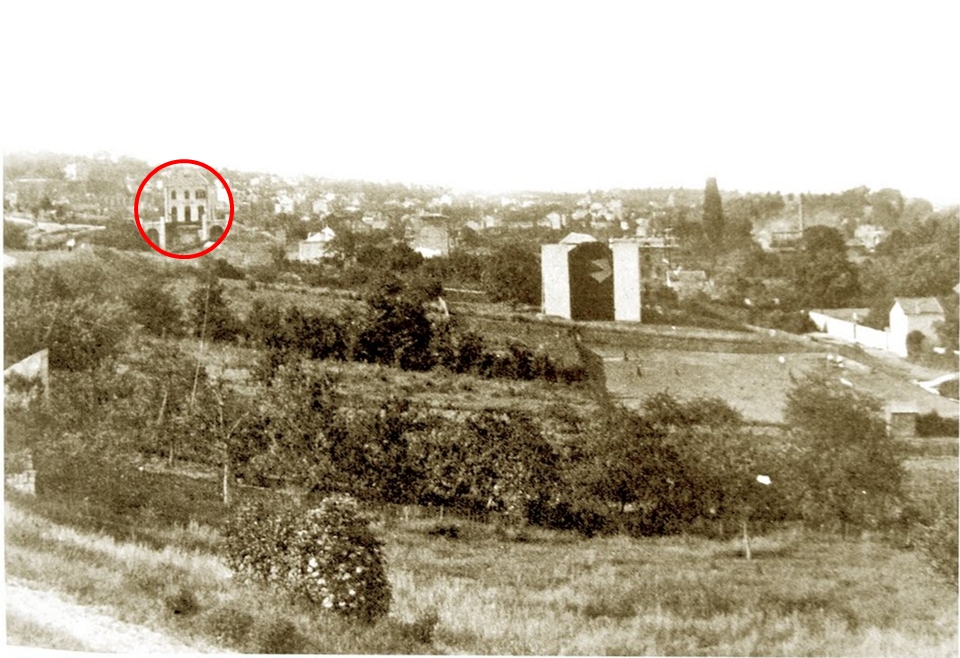

Now here is another well-known photo of the St. Cloud area showing a hangar for balloons. This hangar is often mistaken as the Santos-Dumont hangar. In fact, some postcards of the era declare this is the Santos-Dumont hangar! This very postcard says (roughly) "Hills of Saint-CLoud - the station and old shed of Santos-Dumont". The problem is, it is not the hangar of Santos-Dumont!

Photo credits (above): Public domain

Here is another photo which shows the hangar of Santos-Dumont and its relationship to the location of the train station (encircled in red):

Photo credits (above): Public domain

The photo immediately above provides ample evidence to establish the location of the Santos-Dumont hangar and the previous photo it is at complete odds because the hangars are in completely different locations! Both photos, however, are ripe with exploitable information!

Taking the latter photo, we find that the Train Station, which is the same station as seen in both photos of St. Cloud, and still exists today, provides the following estimation of the location of the Santos-Dumont hangar. The hangar would have been at the northern edge of what is today a soccer field. The hangar is estimated to have been at (Lat Lon) 48.855457 002.221617:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

And the location on Google Maps:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

On the other hand, the balloon shed is found to have been located about here ((Lat Lon) 48.855609 002.219794):

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

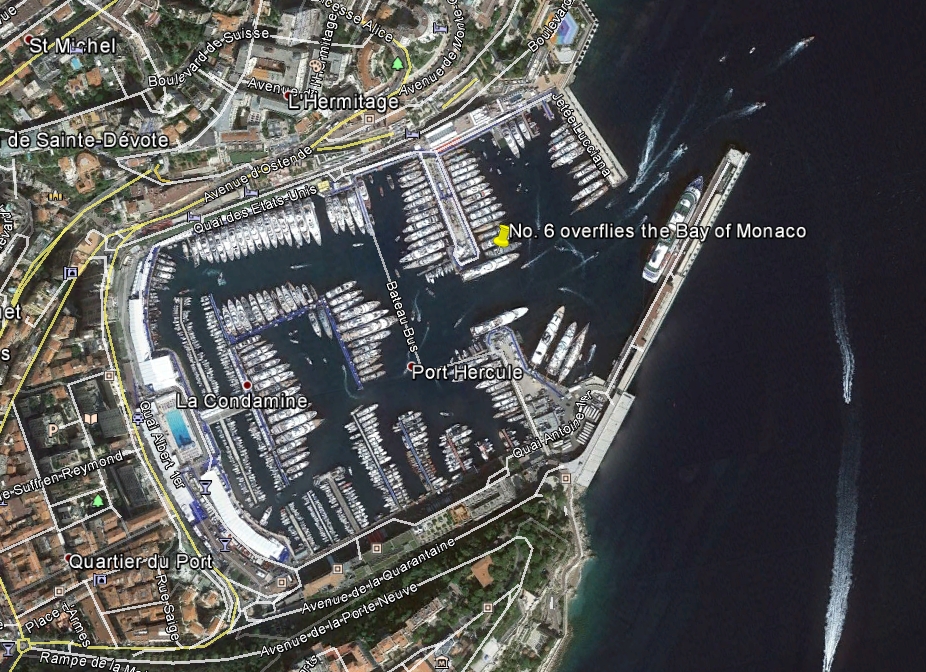

Return to topSantos-Dumont No. 6 at Monaco

In January 1902, Santos-Dumont took his No. 6 to Monaco at the urging of the Prince of Monaco. The prince built a giant hangar for Santos-Dumont on the beach of the Bay of Monaco, complete with giant sliding doors which Santos-Dumont preferred on his airship hangars. There are a few photos of the No. 6 flying around in the bay, as well as photos of the accident in the No. 6 described above. Here is a photo of the No. 6 in the bay:

Photo credits (above): Public domain

So here is the approximate location of the No. 6 in the Bay of Monaco. My estimated location of the No. 6 in the photo is at (Lat Lon) 43.735856 007.427710:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

And the location on Google Earth:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

There is also a photo of the No. 6 as it descends (precariously!) to the hanger on the bank of the Bay of Monaco. It is the only evidence I have to date of the location of the hangar:

Photo credits (above): Public domain

And the location on Google Earth:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

I base this estimate of the location here because a late 1870 plat map of the area indicates a large, flat, open area in this spot. It's the logical place where the Prince Prince of Monaco would build a hangar for Santos-Dumont! It's at (Lat Lon) 43.735013 007.421000.

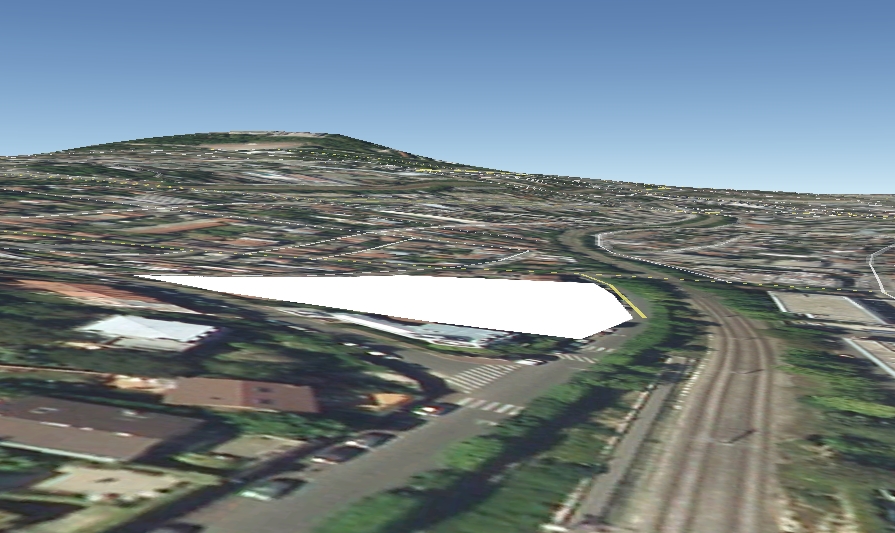

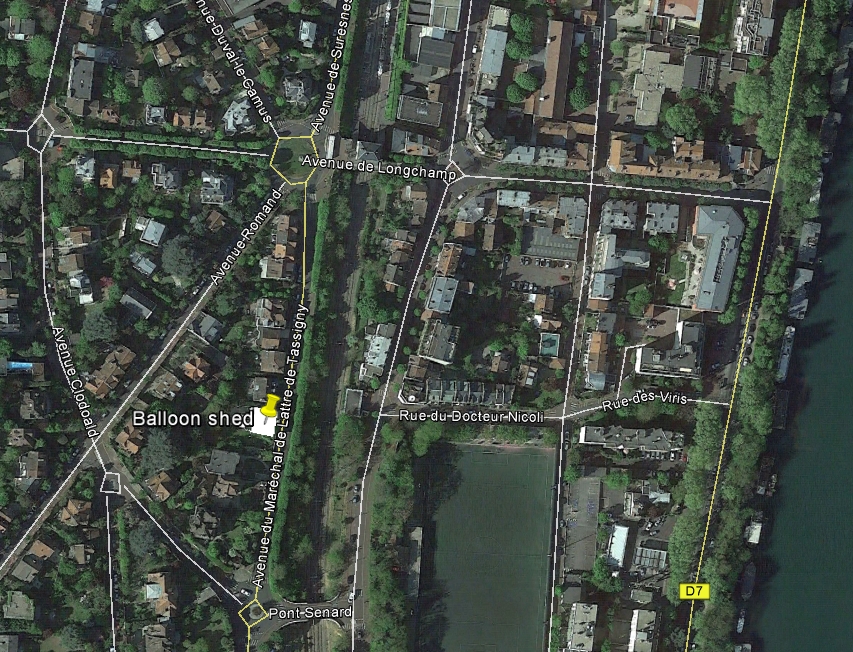

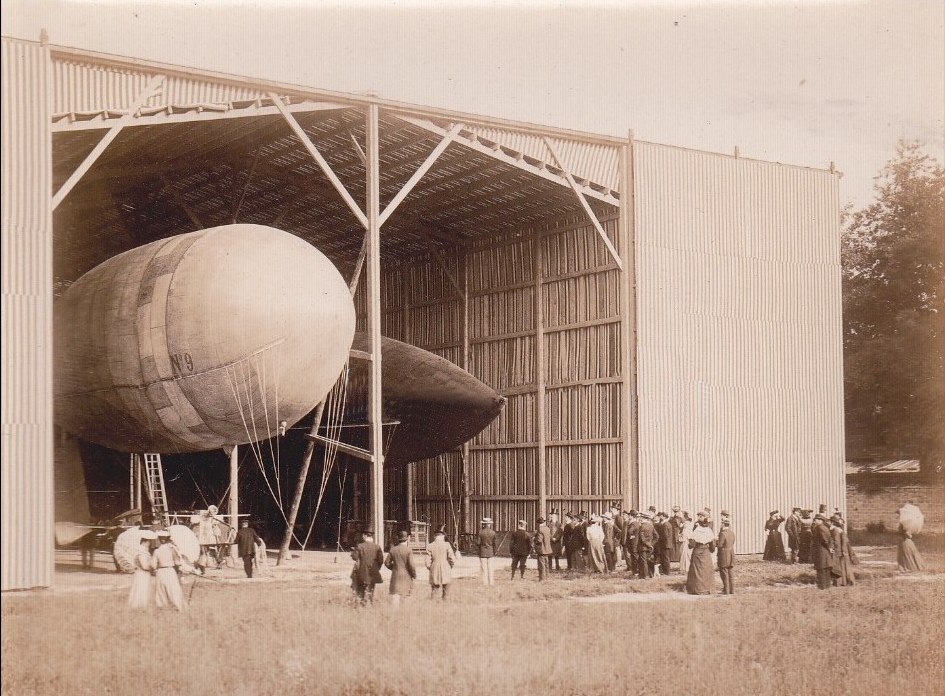

Return to topSantos-Dumont's facilities at Neuilly-St James

In In late 1902, Santos-Dumont relocated his airship facility to Neuilly-St. James. Santos-Dumont gives as his reason for relocating as the cramped and dangerous grounds at St. Cloud though I did see a citation that Santos-Dumont was "kicked out" of St. Cloud! Nevertheless, Santos-Dumont built a giant hangar there and claimed in his book that he could house seven airships, each inflated with hydrogen and ready to fly. (Paul Hoffman, in "Wings of Madness" says there were seven hangars at Neuilly-S.t James but I have found absolutely no evidence of more than two hangars there. See my discussion below on the "Mystery of the Santos-Dumont Hangars".) Of all the photos of the giant hangar at Neuilly, this one is the best as it shows both doors fully open and the No. 9 and the No. 7 airships are plainly visible.

Photo credits (above): Public domain

Try as I might, I was unable to locate exactly the position of the Santos-Dumont operations at Neuilly-St. James! I found what I think is the general area in which he set up his hangar (seen in the white trapezoid, below), but the description of the location in his book "My Airships" defies complete resolution. Here is my current "best guess" of the location centered at (Lat Lon) 48.880442 002.252681:

Photo credits (above): Google Earth

And the estimated location on Google Maps:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

Here's the problem: Santos-Dumont describes the location of the Neuilly-St. James site is thusly:

"After long search I came on a fair-sized lot of vacant ground surrounded by a high stone wall, inside the police jurisdiction of the Bois de Boulogne, but private property, situated on the Rue de Longchamps, in Neuilly St James...

"The Rue de Longchamps is a narrow suburban street, little built on at this end, that gives on the Bagatelle Gate to the Bois de Boulogne, beside the training ground of the same name. To go and come in my air-ships from this side is, however, inconvenient because of the walls of the various properties, the trees that line the Bois so thickly, and the great park gates. To the right and left of my little property are other buildings. Behind me, across the Boulevard de la Seine, is the river itself, with the Ile de Puteaux in it. It is from this side that I must go and come in my air-ships. Mounting diagonally in the air from my own open grounds I pass over my wall, the Boulevard de la Seine, and turn when well above the river. Regularly I turn to the left and make my way, in a great arc, to the Bois by way of the training ground, itself a fairly open space."

I could only match present-day "Boulevard du Général Koenig", renamed from "Boulevard de la Seine" in Santos-Dumont's time and the "Rue de Longchamps" with this description, which indeed does "end" at the Bagatelle Gate to the Bois de Boulogne as described. But as to the north-south position of the facility between present-day Rue du Centre and Rue Bois de Boulogne, this is a complete guess based on the Santos-Dumont plaque hanging on the fence at present-day 89 Boulevard du Général Koenig (Google Maps address). If anyone reading this has any new information on the precise location of the Santos-Dumont complex at Neuilly-St. James, I would be happy to hear from you.

Return to topSantos-Dumont Statue, St Cloud

On the 19th of October, 1913 Alberto Santos-Dumont himself was present at the unveiling of a statue to commemorate his contributions. It was 12 years to the day after his record flight in his airship No. 6 around the Eiffel Tower winning the Deutsch Prize. Santos-Dumont reluctantly spoke to the gathered crowd and was photographed standing next to the statue.

Today, the statue stands in the same location though it is but a facsimile of the original. The original was removed and destroyed during the German occupation of France in WW II. (A careful study of the present-day statue reveals that the bronze of Icarus is not the same casting as seen in the original display).

Photo credits (above): Public domain

Above, the Santos-Dumont statue, the original display, October 19, 1913, St. Cloud France.

The statue today:

Photo credits (above): Georges Colin [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/), CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0) or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The inscription says: "Ce monument à été élevé par l'aéro-club de France pour commémorer les expériences de SANTOS DUMONT pionnier de la locomotion aérienne", [This monument was erected by the aero-club of France to commemorate the experiments of SANTOS DUMONT pioneer of aerial locomotion].

The location on Google Maps, (Lat Lon) 48.856774 002.220032:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

Return to topSantos-Dumont Commemoration of heavier-than-air flight, Bois de Boulogne

My interest is in airships, not heavier-than-air craft but since Santos-Dumont valiantly transitioned from experiments in airships to airplanes I thought it appropriate to highlight the monument to him for his work in winged flight. On the field where Santos-Dumont successfully flew his 14-bis on the 12th of September, 1906 there is a fine monolith:

Photo credits (above): Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vol_de_Santos-Dumont.JPG

And the location of the monument on Google maps, (Lat Lon) 48.868044 002.240111:

Photo credits (above): Google maps

I hope you enjoyed this lengthy page on the Santos-Dumont airships and the locations identified. There are other good photos of Santo-Dumont airships of which I hope to add to this page. There are also many photos which are sadly defying location! Nevertheless, Alberto Santos-Dumont provides a rich source of airship history some of which was recorded. Again, I hope you found this page interesting.